The Kenyan election cycle has become synonymous with bloodletting, but without acknowledgment and apology for the atrocities each time committed, we cannot build any lasting bridges.

taking to forge the uthamaki ideology to keep the presidency within the Gikuyu oligarchy and mobilise the Gikuyu folk around this narrative, thus binding the Gikuyu, Embu and Meru communities (GEMA) in a spiritual and political pact under KANU in an imaginary nation of Uthamakistan.

On July 5th they gunned Tom Mboya down in broad daylight. Although Mboya was a KANU leader, according to David Goldsworthy in Tom Mboya: The man Kenya Wanted to Forget, he had to be eliminated because he posed a threat to the presidency. Killed by a bullet coated in the blood of the oath. Since we have been conditioned to understand politics through the prism of tribe, Mboya’s assassination snapped the already loose cord that tied the Luo to the Kikuyu community after the fall-out of Jomo Kenyatta and Odinga Oginga in 1966 and the mass state-led propaganda Kenyatta and his cabal undertook to paint the Luo community to the Kikuyu as a backward and violent community. The resulting protests against President Kenyatta at Mboya’s requiem mass marked the beginning of animosities that are still felt today.

Although Kenya has remained silent about Mboya’s murder, the effects endure to this day. As Yvonne Owuor, winner of the 2003 Caine Prize for African Writing, aptly observes, after Mboya’s death Kenya gained a third official language after English and Kiswahili: Silence. But I wonder what to expect when a train stops at a lakeside town in 2022. In 1969 the train “offloaded men, women, and children. Displaced ghosts. In-between people. No one to blame. Most of the witnesses were dead. Others had vowed themselves to eternal silence. This was the same as death,” in the words of Yvonne.

After Mboya’s death, the events of 25 October 1969 in Kisumu exacerbated the despair among the Luo. Jomo Kenyatta had come to open Nyanza Provincial General Hospital which had been built with aid from Russia. Although Odinga was not invited, he arrived in force, for it was he who had started the project with Russia’s help. In the ensuing mayhem, the presidential escort and the paramilitary General Service Unit (GSU) shot their way through the crowd, killing many and not stopping the shooting for 25 kilometres outside the town.

If Mboya died, then everything that could die in Kenya did. Including school children standing in front of a hospital the head of state had come to open, lamented Yvonne. The events emptied central province of a people they now called cockroaches, nyamu cia ruguru (beasts from the west). Who spoke of this exile, or of the souls evicted from our world?

The killings were framed as animosity between the Luo and Kikuyu communities, but they were not. It was a group in power using government machinery to crush a perceived enemy. The Luo were not fighting Kikuyu people in the violence that broke out as a large crowd menaced Kenyatta’s security. The security forces killed indiscriminately, hence the “Kisumu massacre”. While the official body count was 11, historians close to the event such as B.A. Ogot put the numbers at 100 people dead. The school pupils along the road at Awasi had come out to sing praises to their president but his security forces silenced them and sent them to their graves instead.

In his book Exclusion and Embrace, Prof. Miroslav Volf captures the experience of the Luo people best when he avers, “We demonise and bestialise not because we do not know better, but because we refuse to know what is manifest and choose to know what serves our interests.” Hence, the proscription of KPU made Kenya a de facto single party state and established a pan-ethnic nationalism. The government accused KPU of being subversive, stirring up inter-ethnic strife, and accepting foreign money to promote anti-national activities, which included the building of the aptly named Russia Hospital that the president had come to open. Having demonised Nyanza Province, it was easy to exclude her from “national” development plans

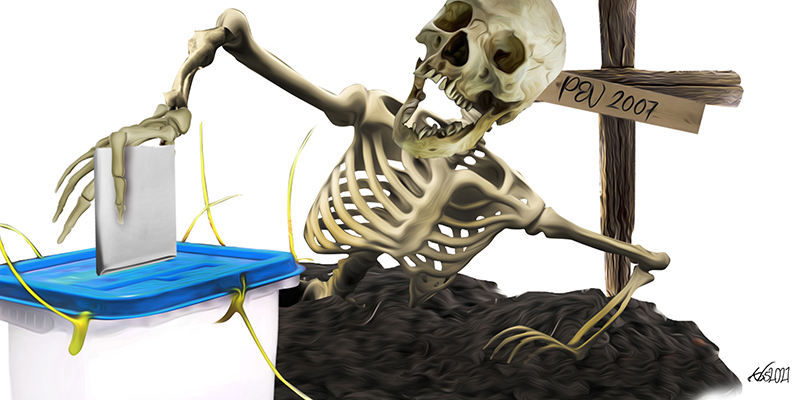

Unless we confront the past, murders like that of the electoral official Chris Musando in 2017 will recur. Kenyan police have a long history of using excessive force against protesters, especially among the Luo in western Kenya. Of the over 1,100 people killed during the 2007 post-election violence, over 400 were shot by police in the Nyanza region. According to Human Rights Watch, in 2013 police killed at least five demonstrators in Kisumu who were protesting a Supreme Court decision that affirmed Uhuru Kenyatta’s election as president. And in June 2016 police killed at least five and wounded another 60 demonstrators in Kisumu, Homabay, and Siaya counties. The state acknowledging these crimes and making public apologies to the Luo will, in my view, end the continued violence against the community.

In December 1970, during a state visit to Poland which coincided with a commemoration of the Jewish victims of the Warsaw Ghetto, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt spontaneously dropped to his knees. Although he uttered no word during his Kneifall von Warschau, his Warsaw Genuflection, Brandt later wrote in his autobiography that upon “carrying the burden of the millions who were murdered, I did what people do when words fail them”. The Kenyan government should do for the Luo what Germany’s leaders did for the Jewish victims of the Nazis.

Even if no one does, we remember. As long as it is remembered, the past is not just the past; it remains an aspect of the present. A remembered wound is an experienced wound. Toni Morrison is right when she says in Beloved that, “Deep wounds from the past can so much pain our present that, the future becomes a matter of keeping the past at bay”. Without apologies, the crimes are bound to recur and our wounds to remain uncovered.

I am terrified by the state’s silence, the wishing away of the crimes and the failure to reach out to the Luo community. While President Steinmeier has called WW II a “German crime” that his nation will never forget, Kenya’s leaders are quiet and want Kisumu forgotten. How can the Luo people forgive crimes no one owns? How can the scar they bear be concealed? I fear that without acknowledgment, ownership and apology, we cannot build any lasting bridges.