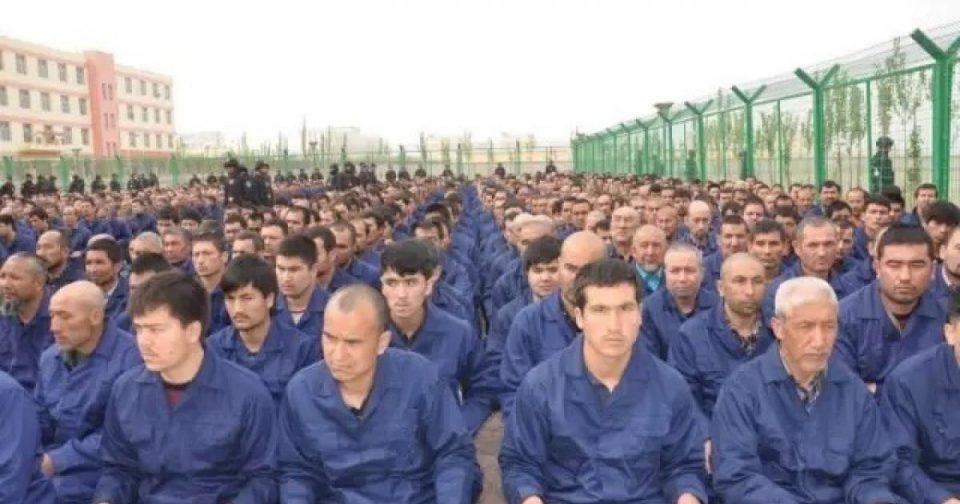

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) clampdown on Uighur and other Muslim minorities in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) has attracted profound scrutiny and polarized the international community. As many as 1.5 million, have been pitilessly detained in large networks of recently constructed camps, where they are forcibly reeducated and politically indoctrinated.

These vexatious developments have not only molded Chinese politics at home but also international politics and debate. Chinese authorities have tactfully pressurized countries with the Uighur population to repatriate them to China. Beijing has established an international coalition to support its draconian policies: when 22 countries had sent a letter to the U.N. Human Rights Council mandating China to refrain from its unjustifiable internments in Xinjiang, that letter was contradicted by another letter from 37 countries defending the Chinese government’s “deradicalization, counter-terrorism, and vocational training policies.” The issue exacerbated tensions between the U.S. and China which lead to the U.S. putting sanctions against individuals and companies coming from China.

The Chinese policies in Xinjiang are glaringly disturbing and repugnant. Any effort to change the situation requires a substantial understanding of the threat perceptions of Chinese in the region, specifically the recent strategy of intensified collective repression.

Decoding China’s Repressive Strategy in Xinjiang

After the XUAR Party Secretary Chen Quanguo returned from the Central National Security Commission symposium in Beijing, the CCP policy in Xinjiang started to spring in 2017. The time frame of this upsurge is puzzling as the public security officials had repeatedly claimed that the strategy was working and there had been fewer cases reported that involved Uighur in Xinjiang, or anywhere in China. Surprisingly, CCP changed strategies after the period.

Various domestic factors have resulted in China’s long-standing security buildup and oppression in Xinjiang: political violence and contention involving the Uighur population in the region; the establishment of second-generation minority policies under President Xi Jinping that made CPP’s turn towards assimilations; and the leadership of XUAR Party Secretary Chen. The increased oppression that took place in 2017, however, was largely motivated by China’s external security threats- most significantly the belief that the terrorist networks may diffuse back into Xinjiang from cross borders.

There are two reasons attributed to the heightened Chinese insecurity. First, the CCP was alerted by the handful of contacts between Uighur and Islamic militant organizations in Southeast Asia and the Middle East in 2014-2016 which also included arrests in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, additionally, up to 5000 Uighur fighting alongside the militant groups in the Middle East.

The connection of Uighur groups abroad to the violent incidents in Xinjiang is highly questionable. The western scholars are doubtful, and even the most generous calculation of Uighur militant capability does not imply that the insurgency inside Xinjiang is present, or even impending. Additionally, the contacts that took place in 2014-16 were confined to a few cases. Nevertheless, these contacts exposed the shift of possibility of cooperation between Uighur and Islamic militants groups in Southeast Asia and the Middle East from completely theoretical to an emerging operational reality. In 2015 and 2016, leaders of several militant groups in the Middle East with some associated with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State also made statements signaling their desire to target China.

The aforementioned developments seem to have got the CCP’s notice. In 2019, the New York Times published leaked documents that quoted Xi saying, “East Turkestan’s terrorists who have received real-war training in Syria and Afghanistan could at any time launch terrorist attacks in Xinjiang.” The documents reveal the fact that despite the Chinese party-state uses the eloquence of terrorism to deflect or reduce international pressure and justify oppressive actions; senior party members including Xi himself fear terrorist threats from abroad subverting their rule at home.

The other element that added to the CCP’s shift in strategy was a change in how the party perceives the nature of domestic threats to regime stability. In 2014, Xi disseminated a new “comprehensive security” framework, which cautioned that international happenings could destabilize regime at home and called for heightened vigilance. The framework required party workers to focus on the increased vulnerability to jihadist infiltration, as they compared it to a virus: even if people showed no sign of radicalism they could still be infected by the extremist virus unless they were properly inoculated.

The two developments reshaped the Chinese perception of counterterrorism and its incidental domestic security policies. As a result, Beijing increased deployment of counterterrorism activities abroad, while at the same time its military delegates visited the Middle East and grew regional counterterrorism cooperation with the Southeast Asian countries. The CCP also targeted diaspora networks to prevent terrorist threats from reentering China; they suggested that detention and reeducation should psychologically and politically make the population resilient to jihadist infiltration.

Eventually, the CCP is unjustifiably imprisoning and forcibly re-educating a large number of people who have merely shown any inclination towards anything except normal Uighur cultural or Muslim religious practice, based on threat perceptions that may be inaccurate in most cases.

The nondemocratic nations often get threat assessments wrong simply because they have difficulties in obtaining good information to initiate with. The very narrative of vaccination, paradoxically, makes that clear: people who are evidently “symptom-free” are nevertheless being thrown in detention and reeducation camps on a massive and intensive scale.

Beijing’s policy of “preventive repression” in the context of counterterrorism took a threat that was at a low level, to begin with, and sought to make sure that it would never materialize into anything more significant. The consequences of this approach have resonated inside China and across the world.

Implications for Current Policies

The United State’s policy concerning Xinjiang should balance two objectives: acknowledging that there may be some genuine concern about terrorism on Beijing’s part and criticizing the use of that concern to justify the indiscriminate repression and collective punishment. The objectives are not paradoxical, but segregating them will require a careful adoption of measures on the part of the U.S. and international policymakers.

Involvement with the CCP’s efforts to curb the terrorist threats doesn’t mean uncritically accepting its response to the problem. Moreover, for the United States or the international community to assist China in fighting terrorist threats, it’s pertinent that Beijing remains transparent. The Chinese security behaviour, characterized by the inability to know the situation may become a hurdle in cooperation against security threats as countries don’t know what will be done in their name.

The United States should focus its rhetoric and policy on the large number of innocent people who are trapped in Beijing’s counterterrorism dragnet. It is pertinent that policymakers make efforts to communicate with the people who have suffered due to Beijing’s draconian policies. The United States and the international community should acknowledge that the CCP’s policies are targeting and punishing people who don’t qualify as “terrorists” under any rational definition of the word. The international community must find ways to exert pressure on Beijing over the human rights consequences of the current measures while at the same time limit its attempts to modify current international human rights norms in a way favourable to it.

The American policymakers and other advocates have, over the past year, shifted their stance towards a simplistic “it’s not counterterrorism” argument that discharges CCP’s insecurities. The engagement of blatant arguments over whether Xinjiang is a case of counterterrorism may not be effective, especially when it appears that the CCP at least partly perceives it that way. The possibility of persuading the CCP to change course on a counterterrorism basis may not be helpful, but the chances of success may be probably higher if the issue is treated solely as a matter of human rights violation.

Though CCP’s emphasis on counterterrorism has largely been instrumental there are risks involved in the current approach. Turning down Beijing’s assertion of security concerns will only set up the CCP to dig in and display graphic images of violence to justify and prove that it faces a real threat. If Beijing successfully convinces domestic non-Uighur audiences in China or in other countries that the Uighur is a threat to security the U.S. dismissals could backfire. Additionally, this approach is neither a helpful tool for American foreign policy nor does it minimize human rights violations in Xinjiang. Consequently, the United States and other democracies should collectively say that no matter how real the CCP perceives the terrorist threats to be, they are not a blank check to approve of Beijing’s massive human rights violations. To add more, the U.S. and European democratic counterparts should keep on pressuring China on the emergence of human rights violation from Xinjiang but to effectively confront the situation they must refrain from getting bogged down in an unhelpful “is it counterterrorism” debate.

Another alternative is that other countries could stress upon the use of indiscriminate repression and false positives in the use of violence, which is commonly backfired: if the CCP is only concerned with regime preservation, the strategy it has adopted in Xinjiang is incredibly risky. For instance, the Uighur who have been targeted unjustifiably after living their lives as “model citizens” may challenge the CCP as a result of being repressed.

The aforementioned approach is of particular significance for countries that must decide on how they take a stance and what are they going to do about the opposing stances adopted by the U.S. and China on this issue. Taking into consideration that most countries are concerned about counterterrorism and seek to be respectful of human rights may align with the United States, weakening the global support for the legitimacy of China’s preferred approach. This will facilitate the United States to emphasize more credibly that Beijing’s linking of international terrorism with its domestic policies of repression poses an unnecessary conundrum for nations that aim to genuinely collaborate with China to reduce common terrorist threats. The mass internment of Chinese Muslims makes it harder for countries with a sizeable Muslim population to approve of the law enforcement and counterterrorism cooperation with China. Turkey, in recent criticism of China’s Uighur Policy, stated the approach as “a great embarrassment for humanity”.

However, if these countries see an increased risk of terrorism at home as a result of cutting off counterterrorism cooperation with China, they may have to face significant potentially difficult tradeoffs. Countries that have significant counterterrorism cooperation with Beijing are mostly absent from the U.N. letter adopting a public stance on Xinjiang. To be realistic, the United States may not be able to convince every country to dramatically change their stance on China’s counterterrorism approach as some of them are well known for their own human rights violations. As a consequence, the United States should try to be on the record for trying to offer realistic alternatives.

The deployment of the aforementioned principles can effectively address the problem of foreign fighters from Xinjiang who participate in Syria and the broader Middle East. This challenge is not confined to China, as it is a global one that reflects the absence of common democratic or international proposal for resolving such glaringly disturbing issues. If international democratic community doesn’t create a mechanism Beijing will tactfully work bilaterally with the countries to simply meet its repatriation demands to punish and re-educate its own nationals, adding to the already devastating human rights violation while leaving the broader global issue unresolved.

Rather than conceding to China’s initiative on this issue, the United States and its allies must lead the way for initiating an international solution to address and validate security concerns among countries. Additionally, the measures should be compatible with human rights: they do not rest on repatriating individuals where they will be persecuted or executed without any justifiable trial. This will lead the United States and the international community to remove Beijing’s internal and external justification for its current policies, making it harder for it to defend at home or abroad.

To sum up, the international community should keep its focus on China’s massive human rights violations in Xinjiang. To do this effectively, it’s pertinent that it must carefully and strategically engage with China’s counterterrorism narratives.

Via- Modern Diplomacy