Book Review

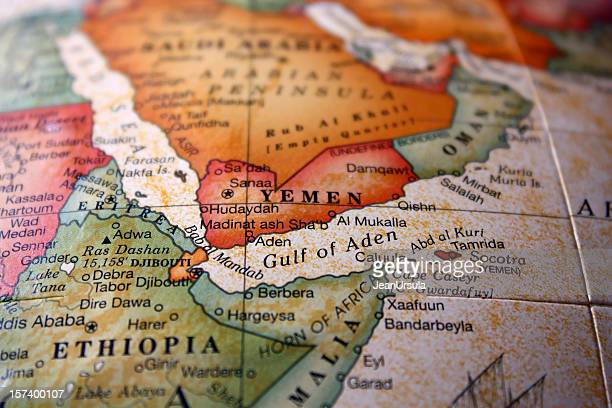

The edited volume provides a solid departure point for those who wisely decide to embark on a journey of jointly exploring the Gulf and the Horn of Africa.

The rebel Houthi movement seized control of Yemen’s capital Sana’a in 2014, launching one of the most devastating civil wars in history that caused the world’s worst humanitarian crisis and rages to this day. Marked by the intervention in 2015 of a deadly Saudi-UAE-led coalition of nine countries, the participation of mercenary African troops (mainly Sudanese) on the side of the international coalition battling the Houthis, as well the emergence of Eritrea’s Assab military base as the launching pad for the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) airstrikes in Yemen escalated the conflict. Although the UAE has since drawn down its support and dismantled the base in 2021, Abu Dhabi continues to play a key military role in Yemen through limited troops on the ground and support for proxy groups in the south. Moreover, a UN Panel of Experts on Yemen has collected substantial evidence revealing that Iran is shipping weapons to the Houthis via coastal towns in northern Somalia.

The conflict in Yemen has drawn renewed attention to the Horn of Africa region.

The conflict in Yemen has certainly drawn renewed attention to the Horn of Africa region. As executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and Horn of Africa expert Alex de Waal puts it: “The war in Yemen sharpened and accelerated a process, already underway, whereby the political rivalries of the Middle East penetrated the Horn of Africa.”[1] For instance, the UAE, aiming at benefiting from Ethiopia’s growing economy and thwarting Qatari and Iranian influences in the Horn of Africa, decisively intervened in the process that culminated in Ethiopia and Eritrea terminating their “state of war” in 2018, ending an almost two decade-long standoff.

Book Cover

The interconnectedness between Gulf countries and the Horn of Africa has become more intense in the last decade, but it is by no means new. Across centuries, continuous flows of people, goods, and cultural and religious influence have kept the regions connected. Although traditionally studied separately, there are now more powerful reasons than ever to approach Gulf countries and the Horn of Africa in conjunction.

This is exactly the task undertaken by an impressive array of scholars in “The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa: Interests, Influence, and Instability,” a recently published volume edited by Robert Mason and Simon Mabon, who are respectively Fellow and Director of The Sectarianism, Proxies and De-sectarianisation (SEPAD) project at Lancaster University.

The Horn of Africa has increasingly become a theater for intra-Gulf geopolitical competition.

“The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa” is structured in two parts, the first considerably longer than the second. In this first section, the authors approach Gulf-Horn of Africa interactions from the viewpoint of Gulf states. One of the key findings of “The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa” is that the Horn of Africa has increasingly become a theater for intra-Gulf geopolitical competition. This is in line with previous work on the subject. As Harry Verhoeven, a professor of government at the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University in Qatar, has noted: “The Horn is no longer a hinterland for key Gulf States but rather an extension of the regional order they seek to build.”[2]

[Understanding Iranian Influence in the Horn of Africa]

[Russia’s Growing Clout in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa]

[The ‘Tug of War’ Over the Horn of Africa and Its Consequences]

In a nutshell, Somalia represents the impact on the Horn of Africa of the intra-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) rivalry that led to the 2017-2021 blockade of Qatar. During this diplomatic crisis, the Arab quartet (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt) applied severe pressure on Doha while Ankara sided with Qatar and provided cargo ships and planes to break the blockade. As Mason explains, in Somalia, “Qatar supports the Somali central government, while the UAE supports autonomous regions in the North.”[3] The de facto northern states, Somaliland and Puntland, have also receivedsignificant support from Riyadh. Turkey, on the contrary, has been supportive of the central state and active in Somalia since the 2011 famine. It recently “built its largest diplomatic premises as well as its second overseas military facility –– where it provides training to Somali security forces –– in Mogadishu.”[4]

If the case of Somalia is paradigmatic of intra-GCC tensions, that of Sudan clearly reflects the ongoing Saudi-Iranian rivalry. In the mid-2000s, Sudan was “an Iranian enclave of influence, as it smuggled weapons to Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon.”[5] In the following decade, however, Saudi Arabia decisively countered Iranian influence by leveraging its deep pockets and diplomatic ties to Washington. Riyadh, contrary to Tehran, was perceived by Sudanese elites as having the ability to “alleviate Khartoum’s economic pressure and political isolation.”[6] Thus Sudan expelled a group of Iranian diplomats in 2014 and severed diplomatic ties with Tehran two years later.

The second half of the volume consists of an exploration of Gulf states-Horn of Africa ties from the viewpoint of the latter. This is a refreshing perspective, as it departs from the kind of analysis that often “takes very little account of the interests and motives of Horn states and their governments.”[7] By approaching Horn states as having agency, we can observe that “Djibouti’s power and influence is disproportionally greater than the state’s small size and ostensibly ‘dependent’ roles would suggest.”[8] The countries of the Horn of Africa have not only been at the receiving end of the intra-Gulf tensions described above, but have also “actively sought to take advantage of the prevailing situation.”[9]

“The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa” raises numerous relevant questions.

“The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa” raises numerous relevant questions. Naturally some of them remain unanswered, thus providing an opportunity for further debate. One of these contested topics is the role of ideology in the relations between Gulf states and the Horn of Africa. Whereas author Marwa Maziad views the antagonistic ideological visions espoused by Al-Sisi’s Egypt and Erdoğan’s Turkey as being an important driver of tensions in the Horn of Africa,[10] Young and Khan see “very little ideology” in the geopolitical rivalries shaping the region nowadays when compared to the Cold War era.[11] This latter view is closer to De Waal’s understanding of the Horn of Africa as a “political marketplace” that is globally integrated through institutions underpinning globalization and, even more importantly, flows of rent.[12]

“The Gulf States and the Horn of Africa” is the first book-length work integrating the study of two regions which, as proven repeatedly throughout the book, cannot be fully understood in isolation. There are a number of factual repetitions across the chapters that could probably have been avoided using an introduction to the volume that comprehensively discusses the principal recent events in both regions. The book, nevertheless, provides a solid departure point for those who wisely decide to embark on a journey of jointly exploring the Gulf and the Horn of Africa.