![Britain was built on the backs, and souls, of slaves A man observes the base of the statue of Edward Colston, after protesters pulled it down and pushed it into the docks in Bristol [Matthew Childs/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2020/6/10/6ddaab79aa63439b9cc18520e1e77ed0_18.jpg)

Some years ago I found myself face to face with the statue that has become the most controversial in Britain after protesters, in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, tore it down and dumped it into a river on Sunday.

Back then though, in Bristol’s harbour, stood Edward Colston (1636-1721), looking every inch the respectable English gentleman, leaning ever so slightly forward onto his cane.

Even then he was a controversial figure because of the two things he is remembered for: slave trading and philanthropy.

Colston was deputy governor of the Royal African Company (RAC) in 1689. The RAC was effectively a private militia, navy and trading company that bought and sold gold, silver, ivory – and enslaved people.

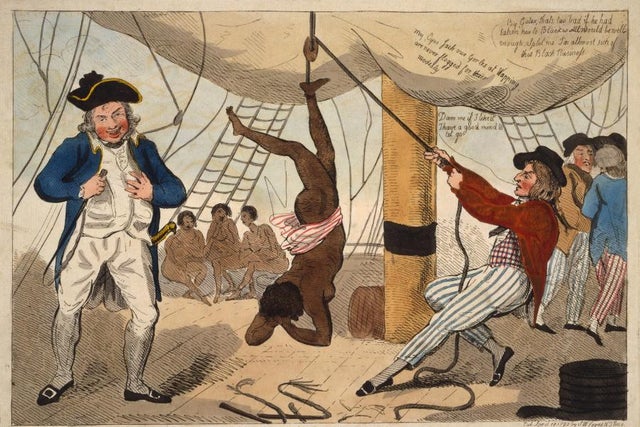

Colston transported enslaved African men, women and children to Bristol, where they were branded with the logo of the RAC, much as you would cattle. According to records from the time, 19,000 enslaved people trafficked from the Ivory Coast died on the journey. Bristol was a hub, not just for Colston and the RAC, but for the global slave trade.

The statue made me angry back then. Erected in 1895, it was a celebration of a man who bought his way into the civic history of Bristol. The statue was erected to celebrate his largesse to the city. He gave generously to charities, educational and health institutions, and they loved him for it.

Britain formally abolished the slave trade in 1807, but only outlawed slavery in 1834, after the Slavery Abolition Act was passed by the parliament the year before.

The British government paid the slave traders 20 million pounds in compensation – 40 percent of its budget. That is some 17 billion pounds (estimated at more than $21bn in today’s money). The government took out a loan to pay it, which was only paid off – by British taxpayer money – in 2015.

That means that living taxpayers in the UK, including descendants of enslaved people, paid billions of pounds to slave traders to stop them from trading in human lives, and to slave owners for the loss of their “property”. Yes. The British government, using public money, paid slave owners but not those who were enslaved.

Among those paid were ancestors of several prime ministers, including David Cameron.

John Gladstone, the father of William Gladstone, who served as prime minister four times during the 19th century, received compensation of 106,769 pounds. That is the equivalent of 83 million pounds today.

Edward Colston died in 1721, but slavery continued for another 100 years. London, Bristol, and Liverpool, which were hubs of the slave trade, became wealthy and powerful.

The backs and souls of enslaved people built Britain – the backs of those who toiled in cotton fields and plantations in British colonies, and the souls of those who did not survive the journey.

Between 1640 and 1807 some 3.1 million enslaved people were transported from Africa. According to the government’s own national archive figures, 2.7 million arrived; the rest died en route.

I remember I had my headphones on the day I stood facing Colston’s statue. At the time some of my favourite music was coming out of Bristol – music rooted in Afro-Caribbean culture but reversioned into something uniquely British by people like me, the sons and daughters of immigrants from Britain’s former colonies.

We do not know if Colston used his immense wealth to try to whitewash his slaver past by building Bristol and through some generous acts of charity, but Britain owes a debt, not just to the descendants of enslaved people, but also to British taxpayers for using their money to make slave traders and owners even wealthier.

As I walked away from the statue that day, I could never have imagined it would meet a watery grave. Now I wonder how many more statues of British slave traders might meet a similar fate.

The article first appeared on AlJazeera