July 17, 2025

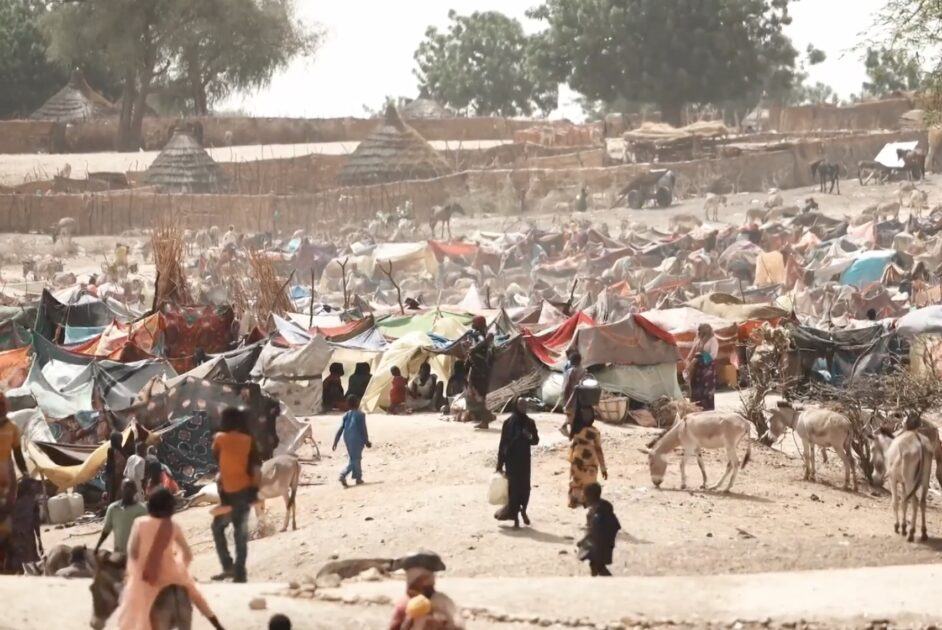

Sudanese refugee camp in Chad. Photo: Henry Wilkins, VOA. Public Domain.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) says over 70% of Sudan’s health facilities are destroyed or barely functioning. Repeated attacks—many by SAF drones—have gutted emergency care. Cholera and other outbreaks are escalating, with hospital-related deaths now 60 times higher than in 2024. These are shocking facts.

Famine stalks Darfur. In Zamzam camp, at least one child dies every two hours. MSF reports a 46% rise in acute child malnutrition. Emergency food centres have shut as convoys are blocked or looted—often by both RSF and SAF-aligned militias. The person I met last week for the first time works tirelessly to keep food flowing through, even growing some of it there.

Since April 2023, 13 million Sudanese have been displaced: 8.8 million internally, 3.5 million abroad. Chad alone has absorbed 1.2 million, with camps like Adré and Tiné overwhelmed and underfunded—only 13% of required aid has arrived. Western politicians sometimes visit these camps—one former UK Africa minister shed a possibly well-timed tear on camera there. The truth is, since Brexit the UK is increasingly sidelined by the rest of Europe, often not in meetings at all, as well as ignored by an increasingly go-it-alone US. Meanwhile, on the ground, SAF checkpoints detain civilians, and RSF loots convoys and forcibly conscripts men in Darfur. Neither Europe nor the US appear either able or interested in doing something about this.

Between April and May 2025, RSF forces bombarded the Zamzam and Abu Shouk IDP camps near El-Fashir. Hundreds were killed, including over 20 children and nine aid workers. RSF then converted the sites into military staging zones and abducted scores of civilians and aid staff.

In Khartoum, RSF-run detention centres have been exposed as torture chambers. Survivors report starvation, beatings, rape, and executions. Over 500 disappearances have been logged in Omdurman alone. I’ve heard firsthand accounts from the Sudanese diaspora in northern England of relatives missing, arrested, or buried in unmarked graves.

On January 24, 2025, an RSF drone strike hit El-Fashir’s last functioning hospital, killing around 70 patients and staff. It marked the collapse of medical care in the region.

SAF abuses are well documented too. In SAF-held zones, detainees face arbitrary arrests, forced confessions, and torture. Aerial bombing campaigns have levelled entire neighbourhoods in Darfur and Kordofan. Human Rights Watch has called SAF tactics ‘blind’ and ‘collectively punitive.’

In April, the RSF declared a ‘Government of Peace and Unity,’ claiming control over RSF-held areas. RSF is led by Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti). His self-declared government now runs in parallel to the army’s Transitional Sovereignty Council. One rumour places him living outside Sudan. SAF leader and de facto leader of Sudan is Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Hemedti’s nemesis.

Frontlines meanwhile shift weekly. In June, RSF seized trade routes near Libya and Egypt. SAF retook roads between Dalang and Kadugli. On July 7, SAF claimed to have captured Kazgeil in North Kordofan.

Despite those trying so hard to help, the humanitarian response is largely failing. Only 14% of Sudan’s 2025 needs are funded. UN Special Rapporteur Michael Fakhri has warned of ‘dystopia’ unless peacekeepers protect aid. With over 360 aid workers killed in 2024—many in Sudan—humanitarian missions are now high-risk. Both SAF and RSF have blocked convoys, looted warehouses, and harassed staff.

To summarise: civilians are under siege. Heavy artillery, airstrikes, hospital bombings, and mass killings are escalating across Kordofan, Darfur, and Khartoum. Health systems are collapsing. Famine is rising. Displacement is historic—13 million people uprooted. Accountability is absent. ICC and UN investigators cite war crimes—especially by RSF—but no ceasefire or prosecution has stuck. Governance is splintering. The rise of a rival RSF government shows Sudan’s fracture, with frontlines replacing any unified rule. The aid model itself is under scrutiny, as air drops and calls for armed humanitarian protection reflect a crisis of trust in traditional logistics.

What’s urgently needed are ceasefires and protected corridors. Civilians and aid must be shielded under international supervision. Humanitarian missions need protection. Assaults on aid convoys should be treated as war crimes. Most crucially, international donors must scale up fast. Just 14% of needs met is unacceptable. And ICC investigations—without constant US sniping—must nonetheless swiftly translate into enforcement against perpetrators on all sides.

This isn’t a ‘romantic tragedy’ of collapse. It’s deliberate, preventable cruelty. And it’s unfolding now. The world has tools—ceasefire enforcement, aid corridors, legal action—but without decisive intervention, Sudan’s collapse will deepen, destabilising the wider region.

I gather most of the exiled civilian politicians I met are as determined as ever to return there, but there appears no sign of this happening any time soon. Former prime minister Dr Abdallah Hamdok once explained to me why a civilian government can be restored: ‘The seeds of democracy planted after 30 years of dictatorship are robust,’ he said. But what no one still knows is when and where it will be safe enough to plant the damned things.