As terrible as these revelations are, what’s more shocking is that he’d never receive that level of compassion today

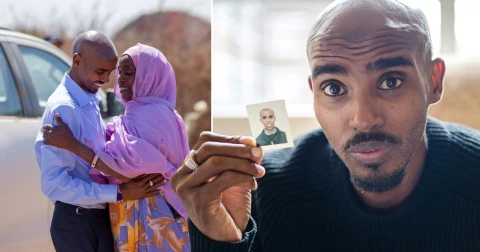

Last Wednesday, Mo Farah revealed in a new BBC documentary that he had not come to the UK as a refugee. He had, in fact, been trafficked to the UK to be a domestic worker when he was a child.

In his heart-breaking testimony, he describes being forced to cook, clean, and care for the children of his employers. He explains how he confided in his PE teacher at school, who then referred him to social services. The documentary shows that Farah’s school repeatedly petitioned the Home Office to grant him British citizenship, so that he could represent Great Britain in international running competitions. And in a particularly powerful segment, he is advised about the potential legal repercussions of sharing his true identity and story. Even now, he learns, the Home Office could revoke his citizenship if it wanted to.

What happened to Farah is shocking and moving. But for those working in the trafficking and exploitation sector, it is also familiar. I hear stories like his all the time in my work at Kanlungan Filipino Consortium, a community-based charity in London that supports domestic workers, undocumented migrants, and trafficking survivors. Many of our clients are Filipino women. Some have been made to work under horrific conditions. Think 12 hours a day for little to no pay, sleeping on the kitchen floor, and subsisting from their employers’ leftovers. They are often brought to the UK by their employers without knowing where they’re going or for how long, and without access to their contract and passports.

But one part of The Real Mo Farah surprised even me: the fact that it worked out. If Farah had spoken to his PE teacher today, rather than in the 1990s, events would almost certainly have taken a different course. Mo Farah, it’s safe to say, would never have been allowed to become Mo Farah.

A pretence of care

Legislation and immigration rules have changed dramatically in the past three decades. The UK now fosters an explicitly ‘hostile environment’ for irregular migrants and refugees, and the support, safety, and pathway to settlement that Farah accessed have all but disappeared for survivors of trafficking and exploitation today. Support systems for even the most vulnerable migrants have been stripped, and in their place successive governments have built up a system focused on immigration enforcement and criminal punishment above all else. The Nationality and Borders Act 2022 is the latest step in that campaign. The widely criticised Part 5 of the act puts a time limit on when survivors can report abuse, gives officers discretionary powers to withhold access to support, and does not guarantee any minimum period of leave to remain.

Odds are that even recognised survivors of trafficking will eventually be forced to leave.

Meanwhile, the main support system the UK offers survivors of trafficking and modern-day slavery, known as the National Referral Mechanism, is unfit for purpose. It is onerous, restrictive, and riddled with barriers to entry. To begin with, potential victims need to be referred into the NRM by a designated ‘first responder’. This includes specialist charities, local authorities, and the police. This is already a high bar for people who may not speak English, have never been to the UK before, and potentially have no way of accessing this information.

Once in, they are given a preliminary decision that says whether their case has enough merit for them to be considered potential victims. If granted, they will receive an allowance of £38 a week, accommodation, access to the NHS, and an offer for counselling. Work, though, becomes illegal once their original visa expires. They then may wait years – and frequently do – before receiving a final decision. But even that does not offer a route towards regularisation. A positive decision from the NRM might strengthen an asylum claim, and a victim might obtain ‘discretionary leave’ of up to 2.5 years to help their recovery. But this leave isn’t renewable and asylum claims are often considered weak. So odds are they will eventually be forced to leave.

The NRM also requires the victim to cooperate immediately and fully with the police and Home Office in order to receive support. This might seem logical to people who have never worked with migrants or traumatised people before, but it’s deeply problematic. It can be incredibly hard to open up about an ordeal, especially in front of strangers, and some of the survivors I’ve supported were so terrified of the authorities that they avoided the NHS and even public transportation out of fear of being identified and detained. What’s more, victims are only protected from immigration enforcement whilst they are in the NRM or have an application pending with the Home Office. If they exit the NRM or have their application refused, they are subject to immigration enforcement and will be easily found because they are now on the radar. Many people refuse to take that risk.

No more Moes?

Today, people who have been through the horrors of trafficking and modern-day slavery are not treated as survivors but rather as suspects of a crime and subjects of immigration control. Farah’s story shows us that a still flawed, yet more compassionate system once existed in the UK, and could exist again. A system where the right supports are in place, where public places like schools are safe spaces for survivors to seek help, and where survivors have people by their side to advocate for their rights.

Farah’s brave, public testimony gives us the opportunity to seriously examine the support offered to victims. We must demand a new vision of support for survivors that responds to their actual needs. For many of the people I support, justice would look like dignity and safety at work and a pathway to settlement, including a way for them to bring their children to the UK. It is time we give them that.