analysis By Meressa K Dessu, Dawit Yohanness and Roba Sharamo

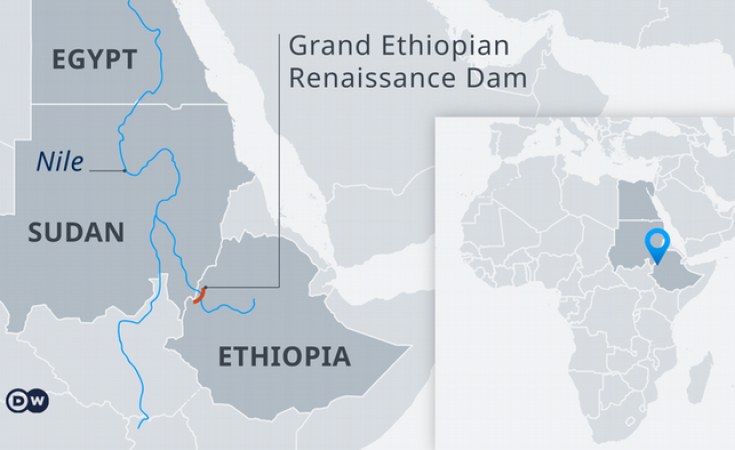

Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan are currently engaged in vital talks over the dispute relating to the filling and operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile River. While non-African actors are increasingly present in the negotiations, the African Union (AU) is playing a marginal role.

In addition to supporting negotiations and the implementation of a possible agreement, there are critical lessons from the negotiations for the AU on how to manage future maritime and freshwater disputes.

With the involvement of the United States (US) and World Bank, the parties have convened over eight rounds of negotiations in two months. Despite making some headway, a conclusive agreement is yet to be signed. Major disputes persist over the timeline of filling the reservoir, and mitigation measures to be taken in case of drought.

The Nile River is a trans-boundary resource shared by 11 African countries including Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan. To date though, there is no approved framework on the water’s management and use. The three countries almost reached an agreement after 10 years of negotiation in 2010. But Egypt and Sudan didn’t sign it mainly due to concerns of ‘water insecurity’ arising from a broader deal affecting their share of water for agriculture, industry and hydroelectric power generation.

Disputes persist over the timeline of filling the reservoir, and mitigation measures in case of drought

In 2011, Ethiopia unilaterally started construction of the dam over the Blue Nile, a major tributary to the Nile. In addition to country-level benefits, Ethiopia claims that the dam has wide significance for regional integration, particularly regarding affordable electricity supply.

While Sudan supports the dam’s construction, Egypt initially rejected it because it considers it an existential challenge. Egypt later accepted the project and the three countries signed a negotiated Declaration of Principles agreement in 2015 – the basis for the ongoing technical talks.

After the tripartite agreement, expert-level negotiations on the safety, filling and operation of the dam were progressing among the countries. But the internal political crisis and ensuing regime changes in Ethiopia and Sudan in 2018 and 2019 respectively delayed the process.

The delays have led to a resurgence of concerns over regional instability. This was raised by Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi when he addressed the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019, leading to his call for international pressure on Ethiopia. A month later, Egypt declared the talks had reached a dead end and requested international intervention.

Russia facilitated meetings between Egypt and Ethiopia’s leaders in Sochi on the sidelines of the Russia-Africa summit in October 2019. The leaders agreed to resume negotiations. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin offered his help, but the two countries settled on US and World Bank mediations.

Since November, five rounds of technical negotiations and over three rounds of ministerial-level meetings have been convened. Although high-level US and World Bank officials have attended as ‘observers’, their role is increasingly seen as providing alternative courses of action to the impasse. After the last round of negotiations, the US said the countries would sign the agreement by the end of February. It now seems more time is needed to finalise the deal.

With its multilateral nature, the AU could be a more neutral arbiter in the dispute

The AU has the primary responsibility to promote peace, security and stability in Africa – anchored in the principle of ‘African solutions to Africa’s problems’. However it hasn’t featured highly in the dam negotiations, with non-African actors instead becoming part of the solution. This is a missed opportunity considering that the AU’s multilateral nature and aspirations to lead on regional stability make it a more neutral arbiter.

The AU’s silence on the issue, at least in public, was especially evident when tensions escalated between Egypt and Ethiopia. The two countries exchanged provocative statements including threats to use military measures to resolve the dispute. In response, the Arab Parliament expressed its concern and offered support to Egypt and Sudan.

Throughout all of this, the AU didn’t issue a single statement. In March 2019 the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) encouraged member states to find peaceful solutions, but the council has since failed to discuss the dispute.

This may show a lack of determination by the AU and its member states to resolve disputes while invoking the rhetoric of ‘African solutions to Africa’s problems’. But the AU may have other reasons for its silence.

According to Institute for Security Studies Senior Research Fellow Andrews Atta-Asamoah, the AU doesn’t have a history of pronouncing itself on sensitive issues. And politics on the PSC means that member states often refrain from placing difficult topics on the council’s agenda, says Atta-Asamoah. Any ‘wrong move’ affects the neutrality, acceptance and utility of the AU in the minds of some member states.

Perhaps the AU doesn’t have the appetite to resolve sensitive disputes between influential states

An African diplomat who wishes to remain anonymous suggested to ISS Today that the AU perhaps doesn’t have the appetite to engage in sensitive dispute resolution between two such influential member states. He also says the AU may lack the capacity to mediate such a complex, technical problem.

But the AU does in fact have the means to support the resolution of such disputes. It could back the negotiation process from the beginning as well as the amicable enforcement of the agreement that emerges. Revisiting the process around these negotiations could help the AU resolve similar maritime and freshwater disputes in future.

The AU and AU Commission chairs could also use their positions to support the negotiations. Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed recently asked South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa – the AU’s 2020 chair – to mediate its disputes with Egypt. This could be a step towards home-grown solutions.

The AU should reflect on the extent and timeliness of its responses to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam negotiations to ensure it isn’t sidelined in future processes involving its member states. It may not always be the lead actor, but the AU’s presence is important to ensure African ownership and leadership in promoting continental peace and security.

Meressa K Dessu, Senior Researcher and Training Coordinator, Dawit Yohannes, Senior Researcher and Roba D Sharamo, Regional Director, ISS Addis Ababa