9 July 2020

‘If he can kill our child, he can kill me as well.’

The threat of violence against women is escalating amid coronavirus lockdowns around the globe. But one region that has lived through a military clampdown for nearly a year – Indian-administered Kashmir – could have foretold the surge.

Being shut in by government order is nothing new in Kashmir, nor is the resulting spike in gender-based violence, women’s advocates say.

The region has seen decades of conflict, militarisation, protests, and violent crackdowns. Kashmir has essentially been on lockdown since August 2019, when India scrapped the region’s semi-autonomous status, bringing the former state of Jammu and Kashmir under direct control of the central government. Authorities imposed a communications blockade and security forces patrolled the streets, shut down public transportation, and closed markets.

Though some restrictions continued to ease in early 2020, India-wide coronavirus lockdowns beginning in March extended clampdown conditions in an already militarised region – and kept survivors of domestic violence shut in with their abusers.

Cases of domestic violence and general violence against women surged tenfold to more than 3,000 a year during a previous clampdown in 2016 and 2017, according to statistics from the Jammu and Kashmir State Commission for Women, a now-defunct government institution established to protect women and children’s rights and ensure quick prosecutions.

Today, Kashmir’s women face both the military lockdown and the pandemic, but there’s little help available for survivors of gender-based violence.

There are no domestic violence shelters in Kashmir. Blockades on mobile phone connections are frequently re-imposed, while movement restrictions hamper NGOs from doing their work. And India disbanded the women’s commission last year along with Jammu and Kashmir’s statehood – axing a government body that advocated for survivors of gender-based violence.

Locked in with abusers

Rafiqa, 39, says the military clampdown and the coronavirus have pushed her to a crisis point with her husband.

She spoke to The New Humanitarian on condition that her and her husband’s names be changed to protect her safety.

Rafiqa said her husband, Mushtaq, started hitting her a year after they were married, in 2006.

“He would often beat me with a leather belt,” she recalled. “Even an argument would lead to serious beating and abuse.”

The violence grew more intense after Mushtaq lost his job last August. Rafiqa said he started demanding that she turn over her salary from her government job.

“I handed over my salary to him. Now, he was asking me to get money from my father,” she said. “I refused. He picked up a cricket bat and beat me.”

Kashmir’s transportation shutdown and a mobile phone blackout that lasted until early 2020 kept Rafiqa from reaching her parents. Finally, she turned to a local religious leader for help.

“He would often beat me with a leather belt. Even an argument would lead to serious beating and abuse.”

Her husband was persuaded to stop hitting her, but he retaliated by pushing their children to distance themselves from her, Rafiqa said. The children are no longer allowed to sleep near her, or help with the twice-weekly dialysis treatments she has depended on for four years. She remains in her home with her husband.

Attorney Vasundhara Masoodi Pathak, who headed the Jammu and Kashmir women’s commission when it was disbanded last year, said she is now flooded with calls from women in need amid the coronavirus lockdowns. She said she rarely received urgent calls directly from women while the commission was operating.

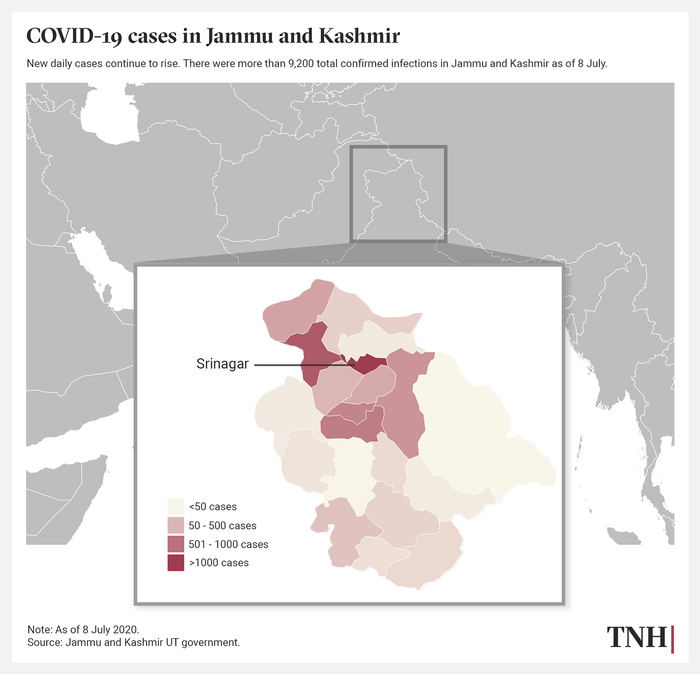

Shops have largely stayed closed and security forces still patrol the streets; an overnight curfew is still in effect as COVID-19 cases rise. Military crackdowns on suspected insurgents, as well as escalating border tensions with China in neighbouring Ladakh – formerly a part of Jammu and Kashmir state – have kept the region on edge.

“In this lockdown, the tormenting husbands and in-laws have got an opportunity to harass women,” Pathak said. “Working women, who before the lockdown would somehow vent their pain and grievance either with peers, family, or friends, now find it very hard to spare even a jiffy to speak out, as they are under continuous and unwanted surveillance.”

Nowhere to turn

Since the women’s commission was shut down, victims of domestic violence no longer have a dedicated avenue for reporting abuse. There is only one women’s police station in the entire Kashmir valley, and male officers aren’t trained to handle domestic violence.

Unless a woman has severe injuries, most male police officers decline to take such reports, telling victims instead that the assaults are a family matter, said Shah Faisal, state director of the Human Rights Law Network, a collective of Indian lawyers and activists who provide legal support to vulnerable populations.

“Since most of the state machinery is engaged to fight COVID-19, there is no quick respite for the victims,” Faisal said. “With [the] women’s commission no more, women have no access to the justice system and are more vulnerable than ever.”

Women who have been attacked also lack access to medical facilities, because many out-patient departments in public and private hospitals have closed.

“Women have no access to the justice system and are more vulnerable than ever.”

The government’s social welfare department reported 16 rape cases and 64 molestations in Jammu and Kashmir during the first month of coronavirus lockdowns, 20 March to 29 April. But Pathak said that government data is almost certainly an undercount, as there has been confusion about how to report gender-based violence during the full military lockdown that followed the region’s August shutdown. The same department reported zero allegations over the six months before the pandemic.

Nighat Shafi Pandit, a women’s advocate and chairperson of the Srinagar-based Help Foundation, said that “COVID-19 has impacted women badly.”

Nighat, who runs a resource centre for domestic violence survivors, said she never feared venturing out to help during the military lockdown last year, but she has restricted herself to her home during the pandemic.

“One cannot meet the need in person and can’t know their needs virtually,” she said. “Even if women complain, we cannot help or reach them because there is no shelter in the entire Kashmir valley where women can take refuge.”

With few resources for survivors, women like Sameena, a 29-year-old Kashmir resident, are trying to break the cycle of violence on their own.

She said her husband started beating her days after their wedding in September.

The abuse continued through the start of the coronavirus pandemic, when she suffered a miscarriage after her husband raped her.

She spent two days in an emergency ward before a doctor discharged her early, fearing COVID-19 infections.

With nowhere else to turn, she went home to her parents – even though they pushed for the arranged marriage in the first place.

“My parents will tell me to compromise, but I have made up my mind” to divorce, Sameena said. “If he can kill our child, he can kill me as well.”

Source: The Humanitarian News