By Emily Estelle

Maj. Gen. Dagvin Anderson, the commander of US Special Operations Command Africa, gave a sobering assessment of the increasing security threats posed by al Qaeda, the Islamic State, and their ilk in Africa in an AEI webinar on September 9 (see the video and transcript here). He warned of African al Qaeda affiliates’ growing responsiveness to their parent organization and highlighted al Qaeda’s “methodical” playbook for coercing and controlling local populations in West Africa while remaining under the US policy radar. Maj. Gen. Anderson acknowledged the US military’s small footprint in Africa and the centrality of non-military challenges in stoking Salafi-jihadi insurgencies, underscoring the need for a clear strategy and more coordination with international partners and the US interagency to combat the Salafi-jihadi threat.

This picture is bleak, but reality is worse. The Salafi-jihadi movement is already expanding and deepening its presence across Africa, and negative trendlines in key African regions will likely create new opportunities for this spread. Here is what the Salafi-jihadi movement in Africa may look like a few years from now if current trends hold:

- Salafi-jihadi groups will have insinuated themselves into local governing structures across large swaths of West Africa’s Sahel region, where they will be implementing their harsh version of governance and establishing an enduring base capable of supporting external attack plotting. The fallout from Mali’s August coup will have disrupted counterterrorism efforts that had delayed but not stopped the groups’ spread. Salafi-jihadi groups will have begun stoking insurgencies in the northern regions of Gulf of Guinea countries.

- The Salafi-jihadi threats in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin will have begun to merge, allowing already formidable armed extremist groups to share expertise and resources across a massive area. Niger, a fragile state and a US partner, will have come under greater pressure from Salafi-jihadi insurgencies on multiple fronts.

- A flawed counterterrorism response in Mozambique will have inflamed an Islamic State–linked insurgency, which will likely have established an enduring territorial presence and become a symbol of the Islamic State’s continued relevance.

- Al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s East African affiliate, will remain entrenched in Somalia and will have continued to develop external attack capabilities, including targeting international aviation.

- Libya will have fragmented even more and external powers will be entrenched. Eastern Mediterranean tensions will have escalated, and the Libya and Syria wars will have helped fuel a full-blown NATO crisis. The Islamic State or its successor in Libya will have regained capability in the chaotic environment and will be seeking to destabilize neighboring states and resume attacks in Europe.

- A new civil war or domestic insurgency will have opened a new front for the Salafi-jihadi movement to expand in a strategically significant African state. Countries at risk for such unrest include Ethiopia, Sudan, and Algeria, which face uncertain political transitions. Other states will have likely begun to intervene in this conflict to pursue regional and international interests, fueling and prolonging the conflict while stoking the Salafi-jihadi threat and raising the geopolitical stakes.

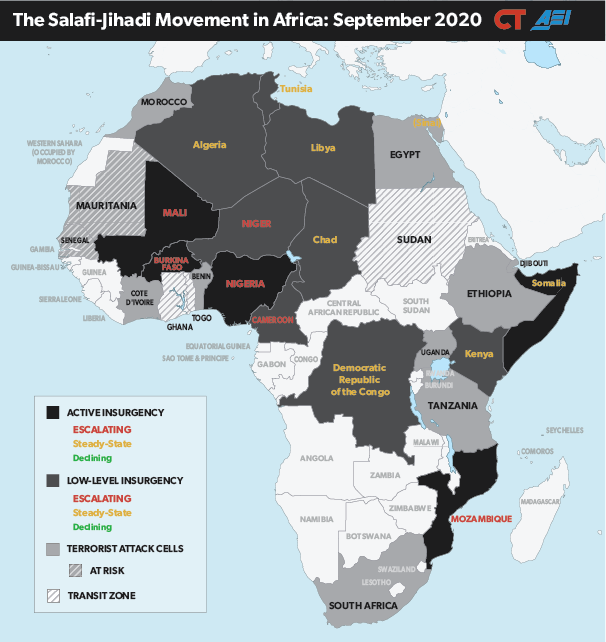

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: September 2020

The US is far from prepared for these likely scenarios. Many will argue that such crises are not our concern. But even beyond their devastating humanitarian effects — which should concern everyone — the past shows that local conflicts that draw in the Salafi-jihadi movement and geopolitical rivals do not stay local. Their effects will be felt beyond Africa’s borders, acutely by our European allies and ultimately in the United States. The destabilization of several African regions will also create opportunities for great-power rivals. While Russia and China may face setbacks from the growing Salafi-jihadi movement in Africa, they will also use countering terrorism as cover to intervene in ways that will fuel the Salafi-jihadi trend rather than arrest it.

The US needs a policy framework for Africa that enables prioritizing and scaling US responses to prevent local conflicts from spiraling into regional crises, as well as rolling back the crises that have already passed this threshold. US Africa Command (AFRICOM) is resource-constrained and likely to face further cuts. In any circumstance, AFRICOM should not be the sole or lead actor for a US approach to African security. The factors that underpin the Salafi-jihadi movement are political, not military. Addressing the fragility that feeds extremism requires a new holistic strategy, and preventing or reducing inflammatory proxy interventions requires both diplomatic leadership and leverage. The US needs to rethink its engagement in Africa — quickly — before the continent’s developing threats are more immediate and more difficult to address.

Emily Estelle recently published “Vicious cycles: How disruptive states and extremist movements fill power vacuums and fuel each other.”