Breaking down the borders between state, society, and sovereignty on the island where trees bleed.

On Socotra, the trees bleed. Known as “Dragon’s Blood Trees,” Socotra’s outlandish Dracaena Cinnabari have seen the island painted by outsiders in fetish and fantasy since time immemorial.

For the uninitiated, Socotra is Africa’s second-largest island. It is also of the Arabian Peninsula, though firmly adjacent – Socotri is among the few remaining South Semitic languages not subsumed into the belly of Arabic. Today there are some fifty to sixty thousand native Socotris. It has often been compared to a land-before-time, a veritable Eden, and has been labeled among the last places on earth to be truly fully explored.

Socotra has often been compared to a land-before-time, a veritable Eden, and has been labeled among the last places on earth to be truly fully explored.

When I first heard of the island nearly a decade ago, it was the absence of information that lured me in. Normally I would forget such a late-night Wikipedia expedition by the following morning, but occasional obscure references served as a steady drip, continuously whetting my appetite. Socotra seemed to have an almost magical propensity to pop up in relation to other odd desiderata that have kept me awake late for no real explicable reason. There is a small often-submerged rock by the same name subject to a territorial dispute between South Korea and China that appeared in some book I was skimming in the SOAS Library when pursuing my Master’s. I stumbled on images of the Soviet-era T-34 tanks on its beaches when researching Russia’s military history in east Africa, ostensibly for a think tank project. I’ve long been fond of employing ambergris, the whale-vomit more valuable than gold, as cocktail party conversation starter — of course, $1.5 million worth of the stuff was extracted from a whale’s stomach on the island recently.

Socotra kept appearing, tantalizing close yet very far away.

Today, there is just one international flight a week, though it goes unlisted on the website of the airline that arranges it, a silent nod to the controversies that rage over Socotra’s administration. When the pandemic struck and borders shut in 2020, and two dear peripatetic friends found themselves trapped with me London, we vowed to go as soon as we could. So this is the story of my own Socotri fantasy — and the lessons about multinationalism, sovereignty, and the role of the state I learned in its telling.

HISTORY AND MYTH

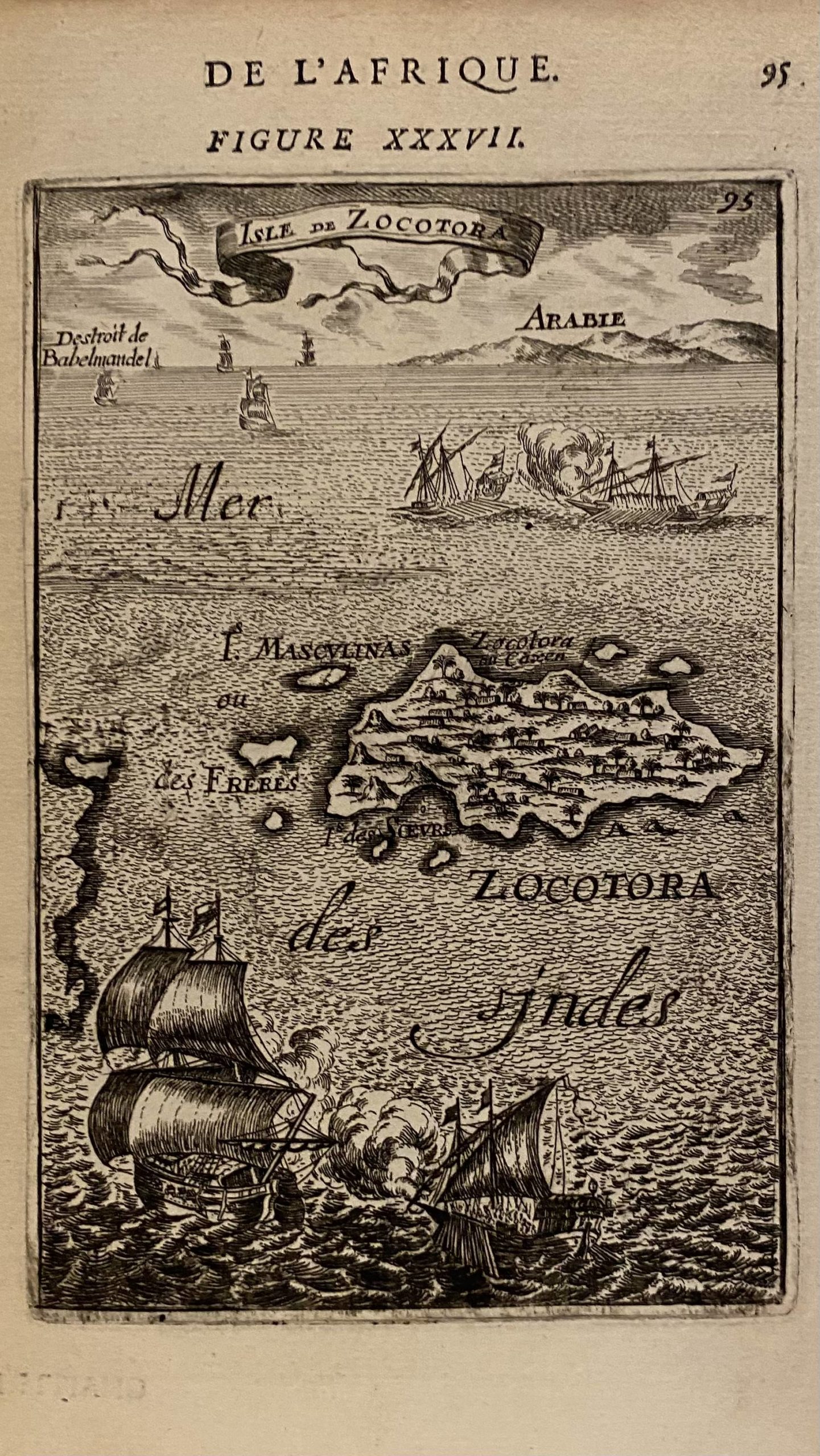

My friends and I were, of course, not the first outsiders to discover Socotra, but I only recently realized how well-trodden the path is. Socotra is found throughout ancient myth and history. Yet the origins of its modern name remain disputed. In fact, cartographers and academics still don’t always agree on its name — other choices include Socotora, Suqutra, or my personal favorite, Zocotra.

A 1683 map from Allain Manesson Mallet’s ‘Description de l’Univers’

Diodorus Siculus noted in the First Century BC that the island was the then-known world’s veritable garden of aromatic plants — in addition to its Dragon’s Blood Trees, Socotra was known for its stores of aloe, frankincense, and myrrh. Later travelers would take inspiration from the island in myriad ways — Gujarati sailors named a sea goddess after the island, where she is believed to live. Dragon’s Blood is found among the ingredients in the varnish responsible for the russet tint of Stradivarius’ world-famous violins.

Portuguese conquistadors who landed on the island in 1507 believed Socotra to be home to cannibals — a belief that remained until not long before the 1958 expedition led by Britain’s Douglas Botting if his entertaining though troublingly supercilious travelogue is to be believed. Britain held a protectorate over the island from the late 1886 century until 1967, after signing a treaty with the Mahra Sultan of Qishn and Socotra. But as Botting acknowledges, they almost entirely forgot about it — perhaps due to an old tradition: the 13th-century merchant chronicler Ibn al-Mujawir reported Socotra was home to sorcerers who could make the island disappear.

Socotra should not be understood as forever moored to the annals of obscurity. Located at the intersection of the earliest active ancient maritime trade routes, Socotra gave much to the world.

However, Socotra should not be understood as forever moored to the annals of obscurity. Located at the intersection of the earliest active ancient maritime trade routes, Socotra gave much to the world. And much that could not be found elsewhere; the level of endemism amongst its flora and fauna compare only to the Galapagos Islands. That Socotra was a thriving destination for trade from the Roman era until the early modern era, is preserved to this day in al-Hoq cave, which bears Indian, Arabian, Ethiopian, Greek and Bactrian inscriptions. A Palmyrene wooden tablet is also among the treasures found within.

So historically, Socotra has been defined not by seclusion but has been firmly rooted in a multinational order. Socotra’s present isolation seems to stand in stark contrast to its ancient position. While monsoon winds have long made Socotra nearly inaccessible from late May through September, in recent years, it has been entirely inaccessible more often than not.

Today, Socotra is part of Yemen, where a civil war exacerbated by foreign intervention rages. The very basic elements of the state are at best fractured, more often non-existent. The market values all of the aloes, frankincense, and Dragon’s Blood that Socotra could sustainably produce in one year less than it does a single oil well. Most of the results when searching Google Images for “Map of Yemen” even forget to include Socotra. It is peripheral even when considering a conflict whose position on the periphery has seen its tragedy all too often forgotten and ignored.

THE TEMPTATION AND THE JOURNEY

It was Socotra’s potential as an escape from the world — there are but two cell phone towers, installed by its most recent external benefactors — that lured me there. The first travel guide was published only in 2020, laughably cruel timing. My daily screen-time went from merely embarrassing to tragic. Images of Socotra shared on Instagram and Whatsapp invited me to a wilder world outside pandemic-induced confines. Dreaming of escaping to an other-worldly, almost preternatural, paradise was infectious.

Eight friends and I ultimately succumbed to the disease. And after enduring COVID-19 testing regimes and travel security regulations across at least seven countries, we arrived in Socotra two days after Christmas.

To describe Socotra as a tropical paradise would be to underwhelm future visitors. It is to Gran Canaria what Gran Canaria is to Canary Wharf. Within 24 hours, one friend asked if we agreed it was the most amazing place we had ever been — no one demurred. A day later the idea that it could be anything but was preposterous.

Resplendent with natural springs and waterfalls, home to 400-meter high sand dunes and adjoining coral reefs caked in tropical fish on whom spinner dolphins feast, dotted with “bottle trees” that prove nature’s imagination more expansive than Dr. Seuss, and inhabited by a proud and protective people, I would already have arranged to move to Socotra if only my beloved dog was allowed to join me. No non-native flora or fauna, save foodstuffs, can be brought onto the island. Locals were also strict that seeds could not be exported — they raised eyebrows when I mentioned that I had read a Dragon’s Blood Tree was growing in Honolulu’s Koko Crater Botanical Garden. It was explained to me the tree takes well over 100 years to grow, but upon my explanatory guess that it was a scientific endeavor, they welcomed the news.

Socotris are not only far more knowledgeable about the outside world than any outsider could ever hope to be about theirs, they recognize that Socotra has value in remaining a world apart. Or, at least, in the rest of us seeing it as such.

THE DISPUTES AND NON-DISPUTES OVER SOCOTRI SOVEREIGNTY

The Yemeni State is absent in Socotra. Not in the same sense as on the mainland, however. Socotra has been almost entirely free of the violence that has engulfed the mainland and hardened its political and sectarian divides. No other state claims sovereignty over Socotra, and while Somalia once submitted claims to its waters in a 2014 declaration to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, no serious contestation is envisaged — Somalia ranks second, just behind Yemen, in the Fragile States Index. There is no Socotri independence movement. The Socotris I was able to question about their views on identity all said they were, of course, Socotri but also Yemeni. To outsiders, however, its sovereignty appears increasingly contested.

All but one of the Yemeni flags I saw on the island were actually the flags of the Southern Transitional Council (STC), one of the main militias in the mainland’s civil war. Seen as close to the United Arab Emirates and occasionally accused of being a proxy for its influence, the STC is a secessionist movement that seeks to re-establish South Yemen. For modern Yemen is among the world’s youngest states, the result of the unification of North Yemen with the theretofore-communist South Yemen in 1990, with the North’s president Ali Abdullah Saleh going on to govern the unified country until stepping down in 2012 following the Arab Spring.

Socotra has witnessed a dizzying array of changes to its sovereignty in living memory. The forgetful British administration came in conjunction with the local Sultan, five of whom ruled from the island in that time, as detailed in anthropologist Nathalie Peutz’s anthropology of Socotra, Islands of Heritage. Peutz’s work outlines perceptions of sovereignty under the four states that have succeeded the Sultanate: The Protectorate of South Arabia that subsumed it, the People’s Republic of Yemen that subsequently evolved into the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, and the Republic of Yemen. The terminal date for the latter merely remains to be determined.

However, formally listing the changes in sovereignty over the island can obscure the reality on the island. Even when last “independent” under the Sultanate, Socotra remained intimately linked to the outside world. Before the late 19th century, Socotra’s ’Afrar Sultans typically ruled from al-Mahra, today Yemen’s easternmost governorate. The family established control over Socotra by at least the mid-16th century and instituted a system of trade and handouts that established a diet based largely on imported foodstuffs.

The Socotris I was able to question about their views on identity all said they were, of course, Socotri but also Yemeni. To outsiders, however, its sovereignty appears increasingly contested.

Socotra’s Sultans also oversaw its earliest “courts” in which those suspected of breaking the island’s social codes were dealt with. A version of Hammurabi’s code applied, with thieves’ hands cut off. Women, without political power, could be expelled from the island on the first passing dhow if they were branded as witches. This practice has long since died out, and it can be a source of embarrassment, given its heterodoxy with the Islamic teaching that has since come to form the core of the islanders’ belief system. Nevertheless, a widespread and devout conviction in local djinn remains. There too remains an attachment to the Sultan today. There were also rumors that he is a modern-day outcast from the island. Who is doing the casting-out went unanswered in my inquiries. He does, however, operate a Twitter account.

Yet even under the Sultans, and their later British overlords, sovereignty remained complex. Wages and handouts were paid in Maria Theresa Thalers, London-minted coins bearing the image of the Hapsburg Empire’s only Archduchess. Examples are retained in Socotra’s only museum, a one-room shack in the settlement of Riqeleh.

Peutz also identifies a unique local conception of the state, which she dubs “the Environment” after the NGOs and UN-backed preservation activity that descended upon Socotra in between 1993 and 2013. It is through “the Environment,” with its shepherding of aid and tourism that most Socotris continue to engage in this practice of hosting and exchanging with outsiders.

The monopoly on abundance appears as important to the Socotri conception of state as the monopoly on violence to Max Weber’s.

MODERN SOVEREIGNTY

Peutz is not the only anthropologist to carry out work in Socotra. Another prominent researcher is Russia’s Vitaly Naumkin, who has detailed Socotri folklore. Its exotic eroticism comes daringly close to blending outsiders’ fetish and fantasy about the island with its native narrations. Naumkin is certainly better known, however, for his role as Russia’s advisor to the former UN Special Envoy for Syria, another land of increasingly complex contested sovereignty over the past decade. Socotra’s tendency to pop out from the marginalia strikes again.

Russia has historical ties to the island as it once hosted Soviet military personnel when South Yemen was the Middle East’s only full-fledged Marxist-Leninist state. After tensions with the US ratcheted up following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the island played host to amphibious landing drills intended as demonstration of Soviet naval power’s reach to the Indian Ocean.

Today Socotra’s only military bases, though it would be a bit of an exaggeration to call them that, belong to the STC. But while the STC might have been in charge of Socotra in terms of having the few local soldiers on the island bearing its insignia, its flags more often than not flew adjacent to an Emirati flag. Emirati flags were in fact far more abundant when taking into account that every third house had one painted on its outside, often their only ornament other than a single typically brilliantly colored iron or wood door.

These painted Emirati flags were described as a way of expressing gratitude. Since a devastating pair of cyclones struck Socotra in 2015, the UAE has provided substantial aid to Socotra, building up its infrastructure including donating a state-of-the-art hospital, and providing its staff, in the capital, Hadibo, one of only two sizable towns on the island, where vestiges of the state are on display. The other, Qalansiyah, is infinitely more pleasant.

Both are adjoined by the aforementioned military baselets. We also witnessed the handout of cash in Hadibo to many men who, we were told, merely collect a wage as nominal military volunteers. The understanding is the UAE finances this. The currency in circulation and in which they are paid is the Yemeni Rial, though many Socotris note there was arbitrage to be had in paying for fuel in Emirati Dirham. Fuel prices anyway were clearly heavily subsidized by the UAE, which provided the fuel. Qalansiyah and Hadibo are both also home to new fish markets, the former Emirati-run, the latter not yet operating. Their scale reveals their orientation to exports.

Our trip to Socotra was also made possible by an Emirati state-owned airline and the few firms that organize travel to Socotra are based there. Tickets and visas can only be procured through these organizers. Along with Socotra’s airport, they also bear the insignia of the Republic of Yemen. This is made easier by the fact the STC has not formally declared independence from the rest of Yemen (though it did unilaterally proclaim autonomy in 2020). Yet questions about the administration of the airport elicited a bewildering array of responses. Various timelines were offered for the UAE controlling it, and frequent mentions too were made of Saudi Arabia.

The Saudi Kingdom has also provided aid to Socotra, and just as we were leaving the Houthis — the side in Yemen’s civil war against whom the STC and Saudi-backed forces are at least mostly united — hijacked one such aid ship. There is also a Saudi compound in Hadibo. However, there were no Saudi flags, though placards detailing some of its donations were on offer in Arabic and English, including at the women’s cooperative store in Hadibo.

There was also much talk of the development of the local real estate market, however. And if the rumors are to be believed, business is booming. Land sales are recorded in a register in Hadibo. When I asked under which authority this was, it was explained to me that it was of course the local practice and questions about whether it was in line with Yemeni law or international law given Socotra is nominally largely off-limits to development since the whole island was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008 did not elicit a clear response. Historically most sales have been to Socotris, or more accurately to their descendants. There is a Socotri diaspora across much of the Gulf, but in particular in Oman and the UAE. Emirati citizens of Socotri descent are the island’s best-known local benefactors, and these ties well precede the present symbiosis.

Reports emerged in the international media in May 2018 that the UAE was planning to occupy Socotra. Emirati Foreign Minister Anwar Gargash dismissed them in a tweet, citing these historical ties as the UAE’s reason for offering support to Socotra. A member of the local special forces echoed these claims as he prepared to fly out of Socotra to the UAE for training with us, arguing that the UAE was helping to prevent the Muslim Brotherhood and Houthis from infiltrating the island.

Nevertheless, speculation about the UAE’s intentions persists.

The UAE would face risks in pursuing any formal annexation, least of all from Yemen’s alternative governments that would surely oppose the move. Though, that breach would likely not stir much in the way of protest, if one only looks to the non-impact of a 2016 ruling by a United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) arbitration panel on China’s claims in the South China Sea for evidence.

Socotra’s unique form of statehood requires a reference point to the outside world. The labels attached to it are less important than the reality of preserving it.

There are potential strategic benefits to the UAE from such an annexation, particularly if the Houthis cement their takeover of much of Yemen, given the interest in ensuring continued safe passage via the Bab Al-Mandab Strait and Red Sea. The UAE has also been investing heavily in northern Somalia, specifically in Somaliland, another place of contested sovereignty, as well as in Djibouti, albeit not without issue.

While Socotra’s future sovereignty is in the air, the UAE already provides the link to and from the outside world, something Socotris require, and for which they genuinely appear grateful.

LESSONS AND EPIPHANIES

Charles Maier, in his timely 2016 book on the history of sovereign borders summarized the controversial German jurist and political thinker Carl Schmitt’s view that “international law was a product of European colonization, whether in the Americas in the 16th century or in Africa in the late nineteenth century.” This is not universally held of course, but Socotra reminds us that international law may not have all of the answers for interstate, let alone intrastate, relations. The concept of the state is too central — and on Socotra, the borders between state, society, and sovereignty break down.

Socotra remains at peace. The Emirati connection is genuine, though geopolitics may determine the future of Socotri-Emirati relations more than historical kinship ties. This could force a new conceptualization of sovereignty onto Socotra. However, were the UAE to surrender its present relationship with Socotra, another outside power — likely Saudi Arabia, which has already been accused of trying to do so — may take its place. Someone must hold the role for Socotra’s traditional relationship with the wider world to continue. Socotra’s unique form of statehood requires a reference point to the outside world. The labels attached to it are less important than the reality of preserving it.

While Socotra remains a dream to which I long to return, it is what the island and its people have to teach the rest of us about multinationalism, sovereignty, the role of the state and — with only modest exaggeration — all other elements of political science, international relations, jurisprudence, and philosophy that has inspired my obsession with it since.

Maximilian Hess is a Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. His research focuses on the relationship between sovereignty, debt, international relations and foreign policy, as well the overlap between political and economic networks.

Source: INKSTICK MEDIA