Secession leads into the unknown and is impossible to predict.

January 9, 2020

Nearly all major ethnic groups in Nigeria have angled for secession at some point, most recently in the south-east. Arguments for secession are usually tribal, political, or even religious, but, at times, advocates point to its potential economic benefits.

In truth, it is difficult to determine whether secession would be better for a region’s economy on balance, or whether the ceded state would grow faster than the country from which it separated. Real-world evidence suggests that secession neither guarantees nor precludes economic progress. The economic success, or otherwise, of a secessionist state depends on the terms on which it obtains its independence and its approach to nation-building after its exit.

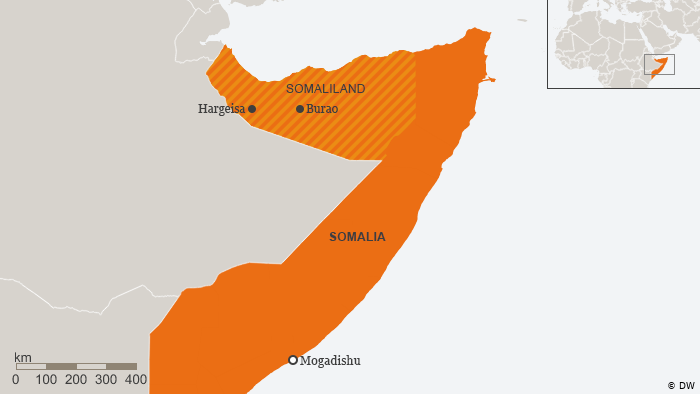

Somaliland, a self-declared country within Somalia, has created a vibrant and stable economy within the failed state of Somalia; conversely, South Sudan sank deeper into war and poverty following its secession from Sudan. How come?

Somaliland quickly built a stable and robust democracy post-independence, allowing businesses to thrive. Meanwhile, the South Sudanese government ignored the importance of fostering institutions and focused instead on how to distribute the country’s oil wealth.

The Price of Uncertainty

Barring a three-year period during the Civil War, Nigeria has existed as a single geographic, political, and economic entity since the 1914 amalgamation. Any attempt at dissolving the Nigerian state as it is would require deliberations on the many economic and social links forged within and between regions in the past century.

The outcomes of these negotiations and the uncertainty they bring would have severe economic implications for all regions. It is nearly impossible to over-emphasise this point: secession would rip apart a century of established economic order and practices. It would be foolhardy to expect this process to be painless.

We can imagine the impact of this uncertainty through the lens of the three primary economic agents in a country.

Businesses are likely to delay investment and hiring decisions, being unsure of the post-secession social and economic environment, and the trading relationship between the two countries.

Consumers have their own concerns too; for example, they might worry about having to convert to a newly established and potentially unstable currency, or about if a government they are no longer citizens of will still pay their pensions.

And government spending will likely be curtailed as lenders will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risk. The secessionist region could bear the brunt of spending cuts as the Federal Government will be reluctant to start any capital projects in the region if secession is imminent.

If these sound familiar, that is because they are some of the arguments used (unsuccessfully) against Brexit, as well as the recent Catalonia debate in Spain. And while the effects of Brexit have surprised most observers – in good ways and bad – the negative economic effects of uncertainty – reduced private investment, hiring, and consumer spending, have been much clearer.

Building a Nation

Beyond the uncertainty secession would bring, the new country would have to face new realities. These include high legacy debts, potentially harsher trading relationships, and a loss of access to revenue from other regions. It would begin its existence with a dent in its revenues, and depending on the terms of exit, may have to fund new services such as national defence.

However, these medium-term negatives could be offset in the long run. The new reality could force the government to take steps to develop a more productive economy. Nigeria suffers from the resource curse and the culture of sharing the national cake among states, which has turned most Nigerian states into mere conduits for distributing oil revenues.

In 2017, only three Nigerian states generated more revenue internally than through FAAC disbursements, indicating that there is little productive, and therefore taxable, economic activity going on in those states. Were they to lose access to oil revenue, for instance, state governments would be forced to create an enabling environment where businesses that will pay taxes and employ its citizens can thrive.

Any new government would also have to cut waste and corruption, and be more responsive to citizens’ needs, given that tax-paying citizens are less tolerant of poor governance and substandard public services.

With a smaller population and less ethnic diversity, government policy can be more tailored, direct and therefore more effective. Singapore, which separated from Malaysia in 1965, is perhaps the best example of a country with no natural resources achieving remarkable economic growth after a secession, by developing a productive economy run by an efficient government.

It’s What You Make It

Secession leads into the unknown and is impossible to predict. Even Brexit continues to surprise everyone. What we do know is that secession may not address the social and economic conditions that engineer it. It will not suddenly create a productive economy, nor will it magically deliver a government committed to building one.

To build a prosperous economy, a secessionist region needs to do the hard work of investing in human and physical capital, implementing effective economic policies, and developing robust institutions – all things that each of the three tiers of Nigerian government has consistently failed to do. To see what a seceded region would look like if its leaders continued as usual, take a look at our states today.

Source:- Somalliland.com