In September 2019, one day before he delivered a speech at the United Nations General Assembly calling out the “violence, cowardice and opportunistic guerilla tactics” of Al-Shabab, the jihadi fundamentalist group gripping large swaths of his country, the president of Somalia was reflecting on his former existence: a life rooted on Grand Island in a two-story home on a street lined with grassy lawns.

His former existence.

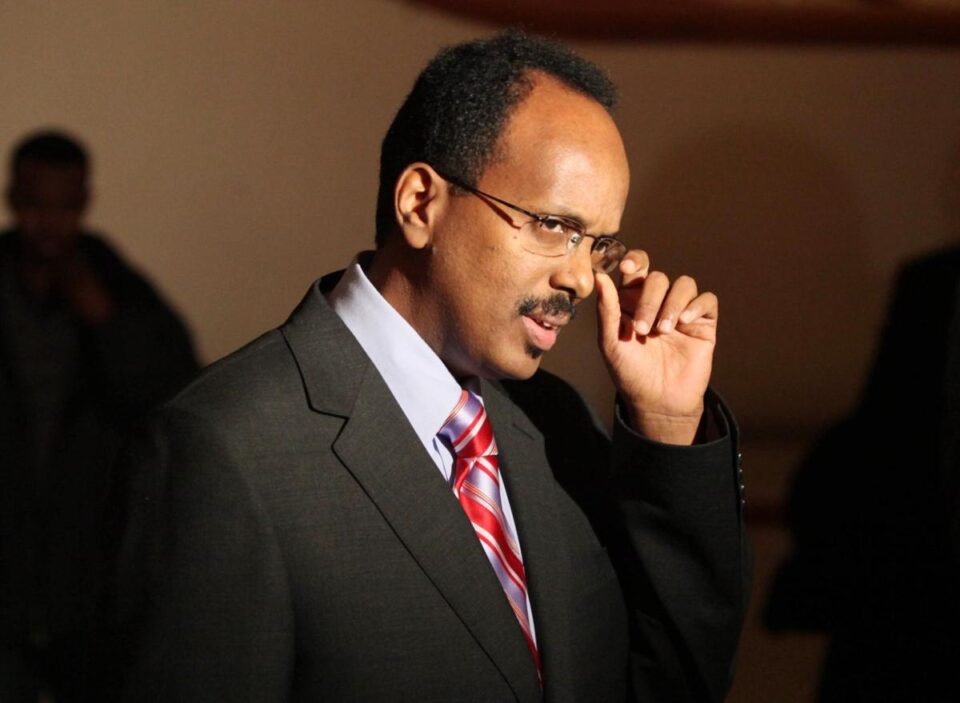

“It is worth it to be in Somalia,” said Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, who spent most of his adult life living in Western New York, where he and his wife raised their family while he worked in midlevel government jobs. “But sometimes when I become overwhelmed, then I remember the easy life, comfortable life, with the family, nice neighborhood.”

That was 19 months ago. If the serenity of Western New York seemed like a faint memory then, it is universes away now.

Back then, Mohamed was touting the opportunity for United States business interests to invest in Somalia. Accomplishing that on a large scale would require snuffing Al-Shabab, which was – and is – responsible for numerous truck bombings, hotel sieges, mall attacks and other forms of terror in Somalia, including the killing of the capital city’s mayor by a suicide bomber.

Mohamed has those battles still. But now there is another: He is fighting for both democracy and – if he cares how Western powers view him – his own reputation. To be pursuing those objectives concurrently seems disjointed: Why would the leadership of someone advocating for a free, safe one-person, one-vote election be so harshly criticized by countries built on the principles of free society?

It’s how he arrived at this point.

Mohamed’s four-year term expired Feb. 8, but because he and the leaders of Somalia’s five member states failed to reach an agreement on how to hold elections, when the calendar hit Feb. 9, there was no new president in charge.

So Mohamed stayed.

Last week, after more election talks failed, the lower house of Somalia’s Parliament passed a resolution extending his term by two years. Mohamed signed it, thus giving himself another 24 months in power – though he insists, “This is not an extension.”

Mohamed, in a series of interviews with The Buffalo News, reframed the two-year addition as a “change in electoral model.” He insists that with the extra time, Somalia can hold “a real, true democratic process in which people can freely vote and elect their leaders,” he said by telephone from Somalia, where he lives and works at the heavily fortified Villa Somalia in the capital city of Mogadishu.

That would appear appealing for Somalia, a war-torn nation in East Africa that hasn’t held a free election since 1969, when Mohamed was 7 years old. But not everyone is buying his pitch. His decision to stay in office beyond his four-year mandate drew the ire of his political opponents in Somalia and other parts of Africa, and skepticism from government leaders in Europe, the United States and from the United Nations. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken issued a scathing statement, which was echoed by the European Union. The Economist, a London-based publication with a large international audience, singled Mohamed out with this headline in March: “A power grab by Somalia’s president has tipped it into crisis.”

Somalia is not a country equipped to absorb more crises; it has plenty already.

Though rich with natural resources from oil and minerals to farmland and nearly 1,900 miles of coastline, Somalia has been wrenched in violence for decades. Mohamed, who was born in 1962 and grew up in Mogadishu, came to the United States in the mid-1980s to work as a junior diplomat in Somalia’s American embassy. When civil war befell his country in 1988, Mohamed received warning that returning home would be too dangerous. He received political asylum in the states and ultimately settled in Buffalo, where he and his wife raised their now-adult children. He became active in local politics, mobilizing the local Somali vote for Democrat-turned-Republican Joel Giambra, who became Erie County executive in 2000. He went to work for the county, and later the state Department of Transportation, overseeing affirmative action and nondiscrimination compliance.

Mohamed also earned a pair of history degrees from the University at Buffalo: a bachelor’s in 1993 and master’s in 2009. He became an American citizen and began developing ideas for how his two countries could work together. In 2010, Mohamed tapped his contacts in Somalia to arrange a meeting at the United Nations with then-Somali President Sharif Sheikh Ahmed. Mohamed wanted to share some ideas with the president from his graduate thesis, “U.S. Strategic Interest in Somalia.”

That meeting, unexpectedly, led to Mohamed getting invited to Mogadishu, where he had not been since the late ’80s. President Ahmed wanted to meet with Mohamed and talk more. Ultimately, Ahmed offered him a powerful job: prime minister.

To call it a gargantuan leap understates the job offer. Mohamed, then the holder of a desk job in a state bureaucracy, was being asked to assume a new title – “Mr. Prime Minister” – and play a key role in the government of one of the world’s most volatile countries. A single incident that happened at the Villa Somalia on that visit portended what was to come: As Mohamed walked across the grounds to his guest house, a shot pierced the air and a bullet whizzed by his head. His escort told him to keep moving and hurried Mohamed to the guest house. The wall in his room was pocked with three bullet holes. “Sometimes it happens,” the man escorting Mohamed told him

Mohamed’s tenure as prime minister was short but noticeable. In 10 months, he pushed hard against Al-Shabab and government corruption, making sure soldiers were paid regularly and on time. But the then-speaker of the Parliament, who had presidential aspirations, cut a deal with Ahmed to extend his term as president by a year. The tradeoff: Ahmed had to ask Mohamed to resign, thus pushing the popular prime minister aside.

Mohamed returned to Western New York, where he resumed his office job with the state but started building his own presidential aspirations. He returned to Somalia for the country’s 2017 election, and emerged from a field of 21 candidates to win the presidency. Among those he defeated was Ahmed.

The way he became president also illustrates the weightiness and dangers of the position. That year, Somalia was to host a national popular election. The people were going to choose a leader. But weeks before the election, terrorist attacks made it too dangerous to open polls across the country, and the election process instead happened inside an airplane hangar, with 300-plus members of Parliament casting their votes in multiple rounds. Mohamed emerged as the winner.

Abdi Ismail Samatar, a University of Minnesota professor who was an independent observer for the 2017 election, accused multiple candidates – including Mohamed – of buying votes. (Mohamed has denied those charges.) Samatar told The News this week that the prospects of holding a one-person, one-vote election in the next year or two are “impossible.”

“The current regime had four years to work on their electoral process,” said Samatar, who recently returned to Minnesota after three and a half months in Mogadishu. He calls Mohamed’s efforts toward democracy “futile” and says the country could have taken steps during the president’s term by holding municipal elections in Mogadishu. “If he and his regime were serious about this election,” Samatar said, “they could have used Mogadishu as an experiment two, three years ago. They didn’t.”

Samatar also points out that Al-Shabab “controls 80%, if not more, of the country,” outside of Mogadishu. “If you couldn’t hold an election in Mogadishu,” Samatar said, pointing to the presence of African Union peacekeepers in capital city, home to more than 2 million people, “how could you claim that you are going to have one-person, one-vote in a country that is as big as the state of Texas?”

Somalia hasn’t had a democratic one-person, one-vote election in 50 years. Mohamed came into office saying he wanted to change that, and put voting in the hands of the Somalian people. But Mohamed and the leaders of Somalia’s five member states couldn’t agree on how to do it. After reportedly reaching a consensus in September 2020, the leaders of two member states – Puntland and Jubaland – expressed concerns and reopened talks, which stretched over the following months and beyond the end of Mohamed’s term on Feb. 8.

“We’re here after our term ended already, months ago, because the country cannot afford vacuum, a power vacuum,” said Mohamed, who claims an act of Parliament last fall allowed him to stay to avoid a leadership gap. “So until an election takes place – until an election happens – we will stay in office because we cannot leave,” Mohamed said. “Who can lead, if we leave? Because you need a legitimate government taking office, legally, through election.”

Last week, after multiple rounds of talks between the member states resulted in no agreement, Somalia’s lower house in Parliament – who also had not been re-elected – passed a resolution extending their own terms, and the president’s term of office, by two years. Mohamed signed that bill into law.

That condemnation was widespread, and some of the most damning words came from the European Union and the United States – allies that Mohamed long considered vital to helping him rebuild Somalia by fighting back against Al-Shabab, and by investing in the country’s oil and other natural resources.

“The United States is deeply disappointed by the federal government of Somalia’s decision to approve a legislative bill that extends the mandates of the president and Parliament by two years,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken said in a statement that noted the move “will pose serious obstacles to dialogue and further undermine peace and security in Somalia.”

Blinken also said: “It will compel the United States to re-evaluate our bilateral relations with the Federal Government of Somalia, to include diplomatic engagement and assistance, and to consider all available tools, including sanctions and visa restrictions, to respond to efforts to undermine peace and stability.”

Mohamed, who gave up his American citizenship halfway though his presidential term as a sign of his loyalty to Somalia, responded to the criticism from the United States and Europe by calling the two-year extension a change in electoral model. “This is not an extension,” Mohamed told The News. “This is a change of election model. This will require time to do this election, of course.”

Mohamed said Parliament’s action, which he signed into law, would allow Somalia more time to plan what he’s been talking about for four years: Holding a democratic, one-person, one-vote election. “The indirect election is not an election,” Mohamed said. “It’s a selection process.” That is because clan leaders are the ones selecting members of Parliament, who in turn choose a chief executive. Because of those multiple layers, he said, “That is not a really democratic election. But this one-person, one-vote is an election that gives every citizen the rights to vote, which we thought the Western countries – the United States and European Union would support – not reject.”

His office’s written statement was harsher, pointing to “inflammatory statements laden with threats” from “international partners and long-time friends” and saying “it is regrettable to witness champions of democratic principles falling short of supporting the aspirations of the Somali people to exercise their democratic rights.”

But does it actually take two years – two more years – to set up free, safe and direct elections?

Mohamed, who wouldn’t specify whether he is going to run for re-election, says it won’t take that long. Following a timeline suggested by Somalia’s National Independent Electoral Commission, he says it can be accomplished in 13 months, or possibly up to 15 months. Because Somalia hasn’t had a democratic election since 1969, he added, that time is needed. “This is the first time in 50 years we have one person, one vote,” he said. “We don’t have … experience in this electoral model.” When asked if he commits to transferring power peacefully if another person is elected president, Mohamed said yes. “Absolutely. Absolutely, absolutely,” he said, “without any hesitation.”

Statements, comments or opinions published in this column are of those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Warsan magazine. Warsan reserves the right to moderate, publish or delete a post without prior consultation with the author(s). To publish your article or your advertisement contact our editorial team at: warsan54@gmail.com

This article has been adapted from its original source