Turkey is building on its already-strong relationship with Somalia as it accepts an invitation to explore for oil in its seas. Ankara has spent years building trust in the region as it seeks to increase its influence.

Turkey’s influence in the Horn of Africa is back in the spotlight, following the announcement that Somalia has invited Turkey to explore for oil in its seas.

The invitation was preceded by a maritime agreement Turkey signed with Libya last year, which increased tensions in the Mediterranean over energy resources.

“This is an offer from Somalia,” said Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. “They are saying: ‘There is oil in our seas. You are carrying out these operations in Libya, but you can also do them here.’ This is very important for us.”

Erdogan did not elaborate as to how Turkey plans to follow-up on Somalia’s offer.

Last October the Somali Minister of Petroleum, Abdirashid Mohamed Ahmed, announced that the country was opening up 15 blocks for oil companies to bid on.

Economic and security developments in the wider Horn of Africa region have boosted the area’s significance as a geostrategic location in recent years. Turkey’s presence has sparked interest from analysts examining its motivations and Gulf States seeking to expand their influence.

Turkish Chief of Staff, General Hulusi Akar and Somali Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khayre tour a newly-opened Turkey-Somali training center in 2017. Turkey has continued to provide military support in Somalia, including training soldiers

Turkish Chief of Staff, General Hulusi Akar and Somali Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khayre tour a newly-opened Turkey-Somali training center in 2017. Turkey has continued to provide military support in Somalia, including training soldiers

Building ‘channels of trust’

Turkey’s close relationship with Somalia is nothing new. It has been a major source of aid to Somalia ever since 2011 when Erdogan visited the famine-gripped country.

What started out as a humanitarian policy grew more complex over time: Soon, Turkey was increasing its aid, founding new development projects and even getting involved in the post-conflict state-building process, becoming one of the first states to resume formal diplomatic relations with Somalia after the civil war, as well as the first to resume flights into Mogadishu. Today, Turkish companies still manage Mogadishu’s main seaport, airport and even provide military training for Somali government soldiers.

“In the case of Turkey and Somalia’s relationship, it has been largely ‘win-win’,” Brendon Cannon, an academic who specializes in external power and their interactions with the Horn of Africa, told DW. “It’s developed rather quickly into an economic relationship. This was helped by Ankara’s direct cash payments to Somalia’s federal government, as well as winning major contracts for infrastructure [projects] in Mogadishu.”

Compared to other international actors, particularly western states, Turkey has sought to build and maintain a sense of trust with Somalia, explains conflict studies professor, Doga Erlap.

“For the past ten years, Turkey has been building channels of trust between Somalia and Ankara,” he told DW. “Turkey is not as wary [regarding issues of security and transparency] compared to the West, putting Turkey a couple of steps ahead of other international ‘bidders’ who may also seek offshore drilling rights in Somalia.”

Horn of Africa a ‘bright spot’

However, what some interpret to be an increasingly assertive and dynamic African foreign policy is more a result of domestic policies.

“Turkey’s primary motivation is domestic at the end of the day. So as a G20 member and as a firm middle power, Ankara — particularly the Ankara ruled by Erdogan — has actively attempted to further Turkish influence in areas outside its normal purview. The Horn of Africa is a particular bright spot in this case, given Turkey’s successes there.”

Erlap says that while Turkey’s global ambitions of becoming a regional hegemon — and reviving its presence in former Ottoman regions — is part of the reason for its interest, energy is the primary driving factor behind Turkey’s decision to maintain its ties to the Horn of Africa, owing to it need for accessible resources.

“The Turkish economy is in a complete shambles right now. So the government desperately needs access to energy resources — one of which is the offshore oil in Somalia.”

Overstating Turkey’s influence

But although much has been said of Turkey’s influence in the Horn of Africa — especially Somalia —some observers are still wary of overstating its influence in the region.

“Like all countries, Turkey has limits to its ability to project power in either a soft or hard form,” Cannon says. “It’s going to maintain resources close to home in the Mediterranean world.”

Turkey has also set its sights on Sudan, where it says it seeks to maintain what Erdogan has described as “deep-rooted relations,” as the war-torn nation begins the long process of rebuilding its state institutions.

“It’s still unclear what Ankara’s interests are with the new government in Sudan and how it’s attempting to sway it one way or another,” says Cannon. “Whether it can compete with what appear to be basically common interests between the Gulf States and Washington and the UK at this point, I don’t believe it stands a chance of being able to do as much.”

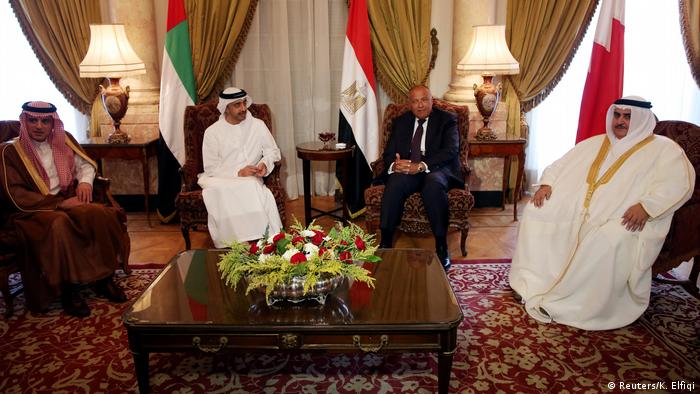

Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir (L), UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahyan (C-L), Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry (C-R), and Bahraini Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa in a meeting. The Gulf States are also expanding their influence in the Horn of Africa

Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir (L), UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahyan (C-L), Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry (C-R), and Bahraini Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa in a meeting. The Gulf States are also expanding their influence in the Horn of Africa

Could tensions in the Gulf lead to increased instability in the Horn?

Turkey’s influence in the Horn of Africa has also been interpreted as a method of countering powerful Gulf rivals such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Since 2017, the Gulf crisis has seen Turkey and its ally Qatar pitted against regional heavyweights Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. Given Somalia’s history as an unstable state and its strategic location along the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which links the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean, it has been used as catalyst of sorts for the regional ambitions of Gulf States. The UAE has accused Somalia of siding with Qatar, while Somalia has also accused the UAE of threatening Somalia’s stability by supporting breakaway state, Somaliland — where it originally planned to build a military airport.

With the feud showing no signs of resolution any time soon, could it possibly spill over in the Horn of Africa as a proxy conflict?

“It could really exacerbate regional and local issues within Somalia itself and then moving across the Horn,” says Cannon. “What Turkey and other external states are doing is not engendering conflict, they’re exacerbating existing fault lines for conflict, and therein lies the trouble.”

Maritime dispute still to be resolved

Somalia’s recent offer to Turkey also risks pulling them into direct conflict with neighboring Horn states such as Kenya, as the oil blocks in question are in the disputed maritime zone — a long-running quarrel which is yet to be resolved in the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The disputed area is approximately 100,000 square kilometers and is thought to contain significant deposits of oil and gas.

While Turkey has been able to focus on development and construction in Somalia without coming to direct conflict with other states in the region, its involvement in securing offshore oil reserves may complicate matters.

“Turkey getting involved in oil blocks and International Court of Justice rulings at this point may bring it into a zone that it doesn’t want to be in,” says Cannon.

Via-DW