By Anup Shah

Jun 21, 2022

J. W. Smith, of the Institute for Economic Democracy, in his 1994 book titled the World’s Wasted Wealth II, has detailed research and summarizes the issue very well and is worth quoting at length:

Highly mechanized farms on large acreages can produce units of food cheaper than even the poorest paid farmers of the Third World. When this cheap food is sold, or given, to the Third World, the local farm economy is destroyed. If the poor and unemployed of the Third World were given access to land, access to industrial tools, and protection from cheap imports, they could plant high-protein/high calorie crops and become self-sufficient in food. Reclaiming their land and utilizing the unemployed would cost these societies almost nothing, feed them well, and save far more money than they now pay for the so-called

Cheap imported foods.

“World hunger exists because: (1) colonialism, and later subtle monopoly capitalism, dispossessed hundreds of millions of people from their land; the current owners are the new plantation managers producing for the mother countries; (2) the low-paid undeveloped countries sell to the highly paid developed countries because there is no local market [because the low-paid people do not have enough to pay] … and (3) the current Third World land owners, producing for the First World, are appendages to the industrialized world, stripping all natural wealth from the land to produce food, lumber, and other products for wealthy nations.

This system is largely kept in place by underpaying the defeated colonial societies for the real value of their labor and resources, leaving them no choice but to continue to sell their natural wealth to the over-paid industrial societies that overwhelmed them. To eliminate hunger: (1) the dispossessed, weak, individualized people must be protected from the organized and legally protected multinational corporations; (2) there must be managed trade to protect both the Third World and the developed world, so the dispossessed can reclaim use of their land; (3) the currently defeated people can then produce the more labor-intensive, high-protein/high-calorie crops that contain all eight (or nine) essential amino acids; and (4) those societies must adapt dietary patterns so that vegetables, grains, and fruits are consumed in the proper amino acid combinations, with small amounts of meat or fish for flavor. With similar dietary adjustments among the wealthy, there would be enough food for everyone.”

J.W. Smith, The World’s Wasted Wealth 2, (Institute for Economic Democracy, 1994), pp. 63, 64.

He goes on to show the effects of imports and exports with regards to food production:

“The United States lent governments money to buy this food, and then enforced upon them the extraction and export of their natural resources to pay back the debt…

Not only is much U.S. food exported unnecessary, but it results in great harm to the very people they profess to be helping. The United States exported over sixty million tons of grain in 1974. Only 3.3 million tons were for aid, and most of that did not reach the starving. For example, during the mid-1980s, 84 percent of U.S. agricultural exports to Latin America were given to the local governments to sell to the people. This undersold local producers, destroyed their markets, and reduced their production.

Exporting food may be profitable for the exporting country, but when their land is capable of producing adequate food, it is a disaster to the importing countries. [Note that many of the poor nations today are rich in natural resources and arable land.] American farmers would certainly riot if 60 percent of their markets were taken over by another country. Not only would the farmers suffer, but the entire economy would be severely affected.

Imported food is not as cheap as it appears. If the money expended on imports had been spent within the local economy, it would have multiplied several times as it moved through the economy contracting local labor (the multiplier effect) …

This moving of money through an economy is why there is so much wealth in a high-wage manufacturing and exporting country and so little within a low-wage country that is on imports. With centuries of mercantilist experience, developed societies understand this well.”

… [S]ubsidies, tariffs and other trade policies eliminate the comparative advantage of other regions to maintain healthy economies in the developed world. … The result of these First World subsidies [for export] are shattered Third World economies.

J.W. Smith, The World’s Wasted Wealth 2, (Institute for Economic Democracy, 1994), pp. 66-67.

(One of the U.S. food programs that J.W. Smith is referring to above is the Food for Peace, or Public Law 480 (PL 480).)

In that final paragraph above, Smith also points out that subsidies to protect industries in the developed world allows products to be produced, which can then lead to dumping on developing countries, whose tariffs etc have been removed due to “free trade” policies and Structural Adjustment, as described earlier.

Anuradha Mittal, of the Institute for Food and Development Policy describes some of the harsh realities of this and is worth quoting at length:

“The victims of free market dogma can be found all over the developing world. An estimated 43 per- cent of the rural population of Thailand now lives below the poverty line, even though agricultural exports grew an astounding 65 percent between 1985 and 1995. In Bolivia, following half a decade of the most spectacular agricultural export growth in its history, by 1990, 95 percent of the rural population earned less than a dollar a day. In the Philippines, as acreage under rice and corn declines and the area under “cut flowers”increases, 350,000 rural livelihoods are set to be destroyed.

Similarly, in Brazil during the 1970s, agricultural exports, particularly soybeans (almost all of which went to feed Japanese and European livestock), were boosted phenomenally. At the same time, however, the hunger of Brazilians spread from one-third of the population in the 1960s to two-thirds by the early 1980s. Even in the 1990s, as Brazil became the world’s third largest agricultural exporter — the area planted to soybeans having grown 37 percent from 1980 to 1995, displacing forests and small farmers in the process — per capita production of rice, a basic staple of the Brazilian diet, fell by 18 percent.

The Mexican government, meanwhile, has put over 2 million corn farmers out of business over the past few years by allowing imports of heavily subsidized corn from the United States. A flood of cheap imported grain has also driven local farmers out of business in Costa Rica. From 1984 to 1989, the number growing corn, beans, and rice, the staples of the local diet, fell from 70,000 to 27,000. That is the loss of 42,300 livelihoods. The same has taken place in Haiti, which the IMF forced open to imports of highly subsidized U.S. rice at the same time as it banned Haiti from subsidizing its own farmers. Between 1980 and 1997, rice imports grew from virtually zero to 200,000 tons a year, at the expense of domestically produced staples. As a result, Haitian farmers have been forced off their land to seek work in sweatshops, and people are worse off than ever: according to the IMF’s own figures, 50 percent of Haitian children younger than 5 suffer from malnutrition and per capita income has dropped from around $600 in 1980 to $369 today.

Kenya, which had been self-sufficient until the 1980s, now imports 80 percent of its food, while 80 percent of its exports are accounted for by agriculture. In 1992, European Union (EU) wheat was sold in Kenya for 39 percent cheaper than the price paid to European farmers by the EU. In 1993, it was 50 percent cheaper. Consequently, imports of EU grain rose and, in 1995, Kenyan wheat prices collapsed through oversupply, undermining local production and creating poverty.

Far from ending hunger and promoting the economic interests of small farmers, agricultural liberalization has created a global food system that is structured to suit the interests of the powerful, to the detriment of poor farmers around the world.”

Anuradha Mittal, Land Loss, Poverty and Hunger, Alternet.org, December 3, 2001

Mittal, quoted above, is also worth quoting again, in an interview:

“Of the 830 million hungry people worldwide, a third of them live in India. Yet in 1999, the Indian government had 10 million tons of surplus food grains: rice, wheat, and so on. In the year 2000, that surplus increased to almost 60 million tons — most of it left in the granaries to rot. Instead of giving the surplus food to the hungry, the Indian government was hoping to export the grain to make money. It also stopped buying grain from its own farmers, leaving them destitute. The farmers, who had gone into debt to purchase expensive chemical fertilizers and pesticides on the advice of the government, were now forced to burn their crops in their fields.

At the same time, the government of India was buying grain from Cargill and other American corporations, because the aid India receives from the World Bank stipulates that the government must do so. This means that today India is the largest importer of the same grain it exports. It doesn’t make sense — economic or otherwise.

This situation is not unique to India. In 1985, Indonesia received the gold medal from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization for achieving food self-sufficiency. Yet by 1998, it had become the largest recipient of food aid in the world. I participated in a fact-finding mission to investigate Indonesia’s reversal of fortune. Had the rains stopped? Were there no more crops in Indonesia? No, the cause of the food insecurity in Indonesia was the Asian financial crisis. Banks and industries were closing down. In the capital of Jakarta alone, fifteen thousand people lost their jobs in just one day. Then, as I traveled to rural areas, I saw rice plants dancing in field after field, and I saw cassava and all kinds of fruits. There was no shortage of food, but the people were too poor to buy it. So what did the U.S. and other countries, like Australia, do? Smelling an opportunity to unload their own surplus wheat in the name of “food aid,” they gave loans to Indonesia upon the condition that it buy wheat from them. And Indonesians don’t even eat wheat.”

…

Remember the much-publicized famine in Ethiopia during the 1980s? Many of us don’t realize that, during that famine, Ethiopia was exporting green beans to Europe. [Emphasis Added]

…

But the deeper issue here has to do with the fact that food aid is not usually free. It is often loaned, albeit at a low interest rate. When the U.S. sent wheat to Indonesia during the 1999 crisis, it was a loan to be paid back over a twenty-five-year period. In this manner, food aid has helped the U.S. take over grain markets in India, Nigeria, Korea, and elsewhere.

Anuradha Mittal, True Cause of World Hunger, Institute for Food and Development Policy, February 2002

More generally, international policies relating to agriculture have been politically weighted towards the more powerful nations who are more influential. While the European Union (EU) and U.S. for example are strong and vocal in demanding that poor countries remove tariffs and other barriers to trade and that it will give them prosperity, they do the opposite. Devinder Sharma, a food and trade policy analyst comments:

“a new Farm Bill pending before the U.S. Congress provides for support of a staggering $170 billion to American agriculture in the next ten years. On the other hand, the EU, paradoxically one of the leading proponents of trade liberalization, has one of the most protected agricultural sectors in the world through its Common Agricultural Policy. Such is the double standard of the EU that it forces developing countries, through the Western-dominated World Trade Organization (WTO), to open up their economies when Europe’s agriculture sector is the most subsidized in the world.

Dollar for dollar, America exports more meat than steel, more corn than cosmetics, more wheat than coal, more bakery products than motorboats, and more fruits and vegetables than household appliances.”

Mattie Sharpless, Acting Administrator, Foreign Agriculture Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture recently told the Senate Agriculture Committee. She also added that agriculture is one of the few sectors of the U.S. economy that consistently contributes a surplus to its trade balance. In fact, the U.S. projections for the current year are that 53% of its wheat crop, 47% of cotton, 42% of rice, 35% of soybeans, and 21% of corn will be exported. This has only been made possible by the heavy subsidies and the removal of trade barriers or QRs in the developing countries.

Devinder Sharma, Food Supremacy, Foreign Policy In Focus, 13 February, 2002

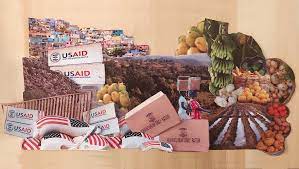

This mercantile process above shows how “AID“can be used as a foreign policy tool.

Farm subsidies have also contributed to surpluses which have been dumped on poorer nations, as discussed in further detail on this site’s section that looks at foreign aid from rich nations. For example, Europe subsidizes its agriculture to the tune of some $35-40 billion per year, even while it demands other nations to liberalize their markets to foreign competition. The U.S. also introduced a $190 billion dollar subsidy to its farms through the U.S. Farm Bill, also criticized as a protectionist measure.

Oxfam illustrates how this can then translate into dumping and other effects:

“Europe’s sugar-production costs are among the world’s highest but, paradoxically, the EU is the world’s second biggest sugar exporter. This is made possible by setting the domestic sugar price at three times international prices, and subsidizing exports of excess production onto the world market. EU consumers and taxpayers are forced to pay the hefty bill of (Euro)1.6bn, but the impact falls hardest on developing countries. This is because the EU sugar regime has the following effects:

- It blocks developing-country exporters, including some of the world’s poorest countries like Mozambique, from European markets,

- It undercuts developing countries in valuable third markets, such as the Middle East, by subsidizing exports to prices below international costs of production,

- It depresses world prices by dumping subsidized and surplus production, so damaging foreign-exchange earnings for low-cost exporters such as Brazil, Thailand, and southern Africa.

… the real winners are a few European sugar processors, and large farmers, who together form a powerful lobby which has blocked change for decades.

…In Jamaica, some 3,000 poor dairy farmers are being put out of business because of unfair competition from heavily subsidized European milk dumped on their market. The subsidies on the 5,500 tons shipped annually cost the European taxpayer $3m. Many of the farmers are women running their own small businesses. They are literally throwing away thousands of liters of milk from overflowing coolers. Many are leaving the industry that has supported their families for decades.”

Europe’s Double Standards. How the EU should reform its trade policies with the developing world, Oxfam Policy Paper, April 2002, p.11 (Link is to the press release, which includes a link to the actual PDF document from which the above is cited.)

In addition, Oxfam also continues (p.12) that White House officials admitted that it would greatly encourage overproduction, fail to help US farmers most in need, and jeopardize markets abroad. According to the European Commission, “there is no doubt that the vast bulk of payments under the Farm Bill

will go to the largest agri-businesses”

Third World producers will find it harder to sell to the US market and, since the USA exports 25 per cent of its farm production, they will find it harder to sell in other international markets or to resist competition from US products in their home markets. The disposal of increased US surpluses as “food aid” is likely to compound the loss of livelihoods”

Poverty and hunger are not just simple economic issues then; they are results of complex factors and decisions and aspects of a political economy; an ideological construct. President Aristide of Haiti faced this food dumping in Haiti as well:

“What happens to poor countries when they embrace free trade? In Haiti in 1986 we imported just 7000 tons of rice, the main staple food of the country. The vast majority was grown in Haiti. In the late 1980s Haiti complied with free trade policies advocated by the international lending agencies and lifted tariffs on rice imports. Cheaper rice immediately flooded in from the United States where

the rice industry is subsidized. In fact the liberalization of Haiti’s market coincided with the 1985 Farm Bill in the United States which increased subsidies to the rice industry so that 40% of U.S. rice growers’ profits came from the government by 1987. Haiti’s peasant farmers could not possibly compete. By 1996 Haiti was importing 196,000 tons of foreign rice at the cost of $100 million a year. Haitian rice production became negligible. Once the dependence on foreign rice was complete, import prices began to rise, leaving Haiti’s population, particularly the urban poor, completely at the whim of rising world grain prices. And the prices continue to rise.

What lessons do we learn? For poor countries free trade is not so free, or so fair. Haiti, under intense pressure from the international lending institutions, stopped protecting its domestic agriculture while subsidies to the U.S. rice industry increased. A hungry nation became hungrier.”

Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Eyes of the Heart; Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization, (Common Courage Press, 2000), pp. 11-12

Note in the above quote, the effect this created dependency has. Free trade and globalization and its effects are discussed on this web site as well.

As a further example, Aristide continues by describing how the eradication of the Creole pigs in Haiti in the 1980s and replacing them with “healthier” pigs resulted in further poverty and hunger:

“Haiti’s small, black, Creole pigs were at the heart of the peasant economy. An extremely hearty breed, well adapted to Haiti’s climate and conditions, they ate readily-available waste products, and could survive for three days without food. Eighty to 85% of rural households raised pigs; they played a key role in maintaining the fertility of the soil and constituted the primary savings bank of the peasant population. Traditionally a pig was sold to pay for emergencies and special occasions (funerals, marriages, baptisms, illnesses and, critically, to pay school fees and buy books for the children when school opened … )

In 1982 international agencies assured Haiti’s peasants their pigs were sick and had to be killed (so that the illness would not spread to countries to the North). Promises were made that better pigs would replace sick pigs. With an efficiency not since seen among development projects, all of the Creole pigs were killed over a period of thirteen months.

Two years later the new, better pigs came from Iowa. They were so much better that they required clean drinking water (unavailable to 80% of the Haitian population), imported feed (costing $90 a year when the per capita income was about $130), and special roofed pigpens.… Adding insult to injury, the meat did not taste as good. Needless to say, the repopulation program was a complete failure. One observer of the process estimated that in monetary terms peasants lost $600 million dollars.

There was a 30% drop in enrollment in rural schools, there was a dramatic decline in protein consumption in rural Haiti, a devastating decapitalization of the peasant economy and an incalculable negative impact on Haiti’s soil and agricultural productivity. The Haitian peasantry has not recovered to this day.”

ean-Bertrand Aristide, Eyes of the Heart; Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization, (Common Courage Press, 2000), pp. 13-15

Statements, comments or opinions published in this column are of those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Warsan magazine. Warsan reserves the right to moderate, publish or delete a post without prior consultation with the author(s). To publish your article or your advertisement contact our editorial team at: warsan54@gmail.com