Paul Currion

13 July 2020

‘The unfinished business of decolonisation is the original sin of the modern aid industry.’

This year, calls for reform of the humanitarian system are proliferating. What’s unusual is that they are not just calls for technocratic fixes but for urgent engagement with real world issues: a new model for humanitarian aid that puts anti-racism at its centre.

Two years ago, I wrote a paper for the Overseas Development Institute, Network Humanitarianism, about the systemic challenges facing humanitarian organisations, the underlying origins of those challenges, and possible solutions. It was widely ignored, but it was exactly what people have been asking for – a new model for humanitarian aid.

I didn’t use the word “racism” once in that paper.

Looking back, I realise I have never written about racism in the aid industry. Yet as the product of a mixed marriage, I have wrestled with my own questions about racism for most of my life. In my personal life, I’ve never been afraid to speak up against racism, even at the expense of friendships. In my professional life, meanwhile, I’ve never been afraid to speak up on other issues, even at the expense of my career.

So the question I now ask myself is: Why? Why did I never put this critical question at the forefront of my writing?

I didn’t because my work focused on those technocratic fixes in aid reform. I didn’t because I thought that the aid industry wasn’t ready to talk about racism. I didn’t because I didn’t think it was my place to. I didn’t because I didn’t want to offend my friends and colleagues. I didn’t because nobody else was talking about it, at least not loudly. I didn’t because I was a coward.

So in my professional life I talked the same language as everybody else – about “localisation”, for example, the aim of which is to ensure that capacity is with those nearest to crisis affected-populations. It’s an admirable goal when seen from one angle; but from another angle, it begs the question of why that capacity isn’t there, and why it seems to be so difficult to achieve. From that angle, “localisation” can look suspiciously like language used to avoid talking about the lingering effects of racism.

As a product of that same aid industry, I made the same sort of rhetorical substitution five years ago when I wrote a column for this publication, Why are humanitarians so WEIRD? The basic argument was that international aid workers are WEIRD – Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic – and that “even aid workers who aren’t WEIRD themselves – the national staff who do most of the work – still work in WEIRD humanitarian organisations.”

What I failed to recognise in writing that column was that WEIRD was my way to talk about racism without using the word itself. The language used by the aid industry left me unable to recognise a conversation about racism even when it was staring me right in the face.

This problem has affected everybody, including non-WEIRD staff themselves, who have found it difficult to raise these issues partly because there was no shared language to discuss them. As recently as 2015, I don’t think the humanitarian community had the vocabulary for this conversation; those who raised it as an issue have been politely tolerated rather than actively engaged with.

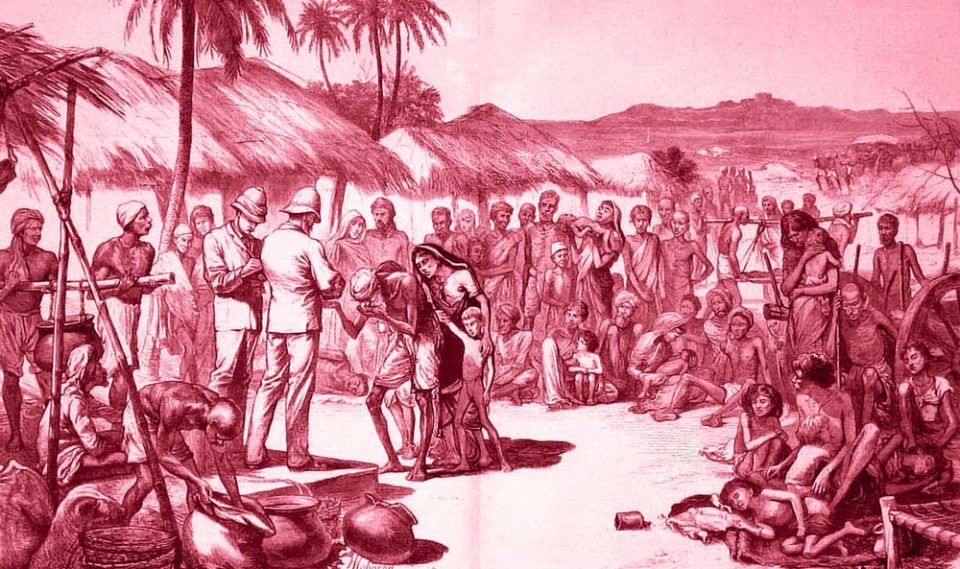

In 2020, I think we finally have the vocabulary, but I suspect that we’re still not ready for the conversation. I don’t think our WEIRD organisations and staff really understand what we’re really talking about when we talk about racism: the unfinished business of decolonisation, the original sin of the modern aid industry as the direct descendant of the old European empires.

The language used by the aid industry left me unable to recognise a conversation about racism even when it was staring me right in the face.

You can see this line of descent from many angles: in how aid flows frequently map to soft power relationships between former colonial powers and former colonies; in how the career trajectory of many international aid workers often resembles that of colonial administrators; in how the “beneficiary” has been constructed as a post-colonial Other; in how local civil society is shaped to fit the mold of “the NGO” rather than more culturally appropriate or politically effective forms; in how “national” staff must learn how to conform to “international” norms in order to be allowed access to positions of power within international organisations.

My concern is that addressing the issue of racism in the aid industry won’t go far enough. The language of anti-racism can and will be co-opted by corporate processes – the endless round of training courses, workshops, and conferences that all of us are familiar with. So although I can’t imagine the decolonisation of aid without aid organisations becoming anti-racist, I can imagine an anti-racist aid organisation that does not work towards the decolonisation of aid. In fact, I can imagine the opposite: an anti-racist aid organisation that continues to operate as an unwitting extension of empire.

For example, Black Lives Matter began with the very specific – and very urgent – concerns of Black communities in the United States over police brutality. What BLM means in Kenya or South Africa is for activists in those countries to say. Police brutality there is an equally urgent concern, but it is not weighted with the white supremacy it possesses in the US.

Yet if anti-racism is framed in distinctly American language, and while the US – despite its rapid decline – is effectively the only remaining imperial power, exporting that language to other contexts risks extending the cultural hegemony of the US. This is a form of epistemic violence itself: in the words of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, “language carries… the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in our world.”

The thread that can connect BLM movements in those and other countries is that police forces in former colonies inherited colonial structures and discourses, and they are therefore descended from the colonialism that gave institutional form to racism. And if the aid industry is similarly descended from colonial structures and discourses, this offers a clue to the reform the industry needs to adopt: not just anti-racism, but decolonisation.

Anti-racism is necessary but not sufficient for the aid industry to make the fundamental changes to move beyond its colonial legacy.

Decolonisation means that the aid industry must take seriously the exhortations of the theologian and social critic Ivan Illich. Speaking in 1968, Illich told US volunteers in Mexico that they must “voluntarily renounce exercising the power which being [WEIRD] gives you… [to] give up the legal right you have to impose your benevolence… to recognize… your incapacity to do the ‘good’ which you intended to do.”

The first round of decolonisation was painful – so painful that it went unfinished. So now we need a second round.

The anti-racism conversation makes a lot of people uncomfortable. The decolonisation conversation might make them leave the room. But maybe that’s the point.

Paul Currion is an occasional TNH columnist and independent consultant to humanitarian organisations. A recovering aid worker, he has responded to crises in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Indian Ocean Tsunami.

The article first appeared in the Humanitarian News