Djibouti, located at the far end of the Horn of Africa, is the country with the smallest acreage on the African continent. But its proximity to the Middle East, its location on the energy transit roads, and its position on the Bab al-Mandab Strait all make this country of great importance for global powers.

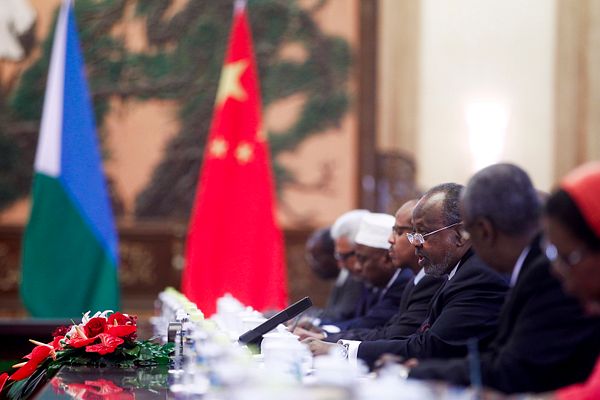

In recent years, China-Djibouti relations have developed and achieved fruitful results in various fields. In 2017, China established a naval base in Djibouti, representing the first time it has sought a permanent military presence beyond its borders. The two countries also agreed to establish a strategic partnership to strengthen all-round cooperation in the same year, ushering in a new era in China-Djibouti relations. Djibouti also actively participates in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Sino-Djibouti relations must be examined in the broader context of Beijing’s vital economic interests in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. China has expanded relations with Djibouti primarily through growing economic ties under the BRI framework. Djibouti offers China a commercial hub for its overseas investment and economic interests in the African continent for several important reasons. First, Djibouti’s strategic location is the most critical asset for Chinese economic interests, being located at the crossroads of one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. A significant percentage of Beijing’s trade with the European Union, valued at over $1 billion a day, passes through the Gulf of Aden, and 40 percent of China’s total oil imports pass through the Indian Ocean. Djibouti controls access to both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, and links Europe, the Asia-Pacific, the Horn of Africa, and the Persian Gulf. Its geographical location at the mouth of the Red Sea mouth makes Djibouti an ideal transshipment hub for cargo in and out of the MENA region and offers long-term growth potential as the economic momentum in the proximity intensifies over time.

Second, since the launch of the BRI in 2013, Djibouti is a critical logistic and trading hub in Beijing’s new Silk Road strategy, which envisages the strengthening of maritime trade routes stretching from China to the Indian Ocean, then to the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea, and through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean. The Chinese naval base in Djibouti helps increase trading through the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. Separately, a $3.4 billion railway line running from Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to Djibouti City plays an important part in maximizing Djibouti’s strategic position within the BRI framework.

Third, Djibouti has general strategic importance for China’s energy security, thanks to its location along heavily trafficked sea-lanes, Red Sea waters, and the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. Although only 4 percent of Beijing’s natural gas imports and 3 percent of its crude oil pass through the strait, Djibouti facilitates the transport of crude oil through the strait and protects oil imports from the MENA region that traverse the Indian Ocean on their way back.

Finally, the Sino-Djibouti strategic partnership is much more than establishing a naval base; it strengthens Djibouti’s position as a critical entry point in infrastructure, which will expand the country’s trade and logistics capabilities. Most of Djibouti’s major infrastructure projects, which have been valued at $14.4 billion, are funded by Chinese banks, including the Ethiopia-Djibouti railway project mentioned above. Beijing is also funding a pipeline to transport natural gas to Djibouti’s port for export to China.

Recently, a Chinese company agreed to finance Djibouti port’s revamp, one of the many development projects involving Chinese companies. China Merchants Group, China’s biggest port operator, signed a $350 million investment deal with the state-owned company Great Horn Investment Holding to turn the Port of Djibouti into an international business hub. The port is located in Djibouti City, part of a $3 billion development project that also includes a free-trade zone and business center. For the Chinese company, which owns a 23.5 percent stake in the Port of Djibouti, this venture offers opportunities and economic benefits in developing, operating, and managing the redevelopment project, given Djibouti’s prime location, stable geopolitical environment, and the largest deep-water port in East Africa.

Chinese companies and banks are involved in a variety of other infrastructure projects in Djibouti. An undersea fiber optic cable laid by Huawei Marine Networks, and financed by China Construction Bank, connects the East African nation with Pakistan, part of its new 12,070-kilometer Asia-Africa-Europe cable. China Merchants Ports Holdings is funding the $590 million Doraleh Multi-purpose Port. The Chinese port operator is also developing a $3.5 billion Djibouti International Free Trade Zone, expected to be Africa’s largest free-trade zone. Other investment projects backed by Chinese firms include port facilities, a railway, and two airports, as well as a pipeline to supply water from neighboring Ethiopia.

China’s extensive investments in Djibouti are a microcosm of how it has rapidly gained an economic foothold across the African continent. China is the largest trading partner of Africa as a whole. Eastern and southern African countries, in particular, have seen many Chinese investments in infrastructure projects. According to the Africa Attractiveness report 2018, China was the largest investor in terms of total capital. In some parts of the economy, Beijing has become ubiquitous, winning many construction contracts (e.g., roads, bridges, airports, housing estates, etc.); in infrastructure investment projects, Chinese companies work on schedule and at unbeatable costs. In exchange for concessional loans to finance projects for its partners, Beijing signs lucrative contracts to supply raw materials.

U.S. officials have raised concerns that Djibouti’s infrastructure projects, financed by Chinese banks, are causing the tiny East African nation to fall into a debt trap that will allow China to reinforce its influence on the continent. Djibouti’s debt to China has reportedly increased to more than 70 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). According to the China Global Investment Tracker, however, the total Chinese investments and contracts in Djibouti from 2013 to 2020 were worth $1.02 billion, mostly in the transport sector.

In the end, the tiny East African country is pursuing an ambitious agenda, “Vision Djibouti 2035,” to transform itself into a commercial trade hub for the rest of the continent. Djibouti also seeks to develop into a middle-income economy and a regional transport and logistics hub. This corresponds to China’s strategy of expanding investment in Africa and the new Silk Road strategy, especially its maritime trade component. Thus, Djibouti’s ambitious plan is being financed mainly by China, which plays a growing role in the tiny East African country. Beijing’s engagement is multifaceted, ranging from significant infrastructure investments to the establishment of its first overseas military base.

Dr. Mordechai Chaziza holds a Ph.D. from Bar-Ilan University and is a senior lecturer at the Department of Politics and Governance and the division of Multidisciplinary Studies in Social Science, at Ashkelon Academic College, Israel. He is the author of the books “China and the Persian Gulf: The New Silk Road Strategy and Emerging Partnerships” and “China’s Middle East Diplomacy: The Belt and Road Strategic Partnership.”

This article has been adapted from its original source

Statements, comments or opinions published in this column are of those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Warsan magazine. Warsan reserves the right to moderate, publish or delete a post without prior consultation with the author(s). To publish your article or your advertisement contact our editorial team at: warsan54@gmail.com