Contrary to the evidence, the president said the U.S. was not at war, writes Joe Lauria.

By Joe Lauria

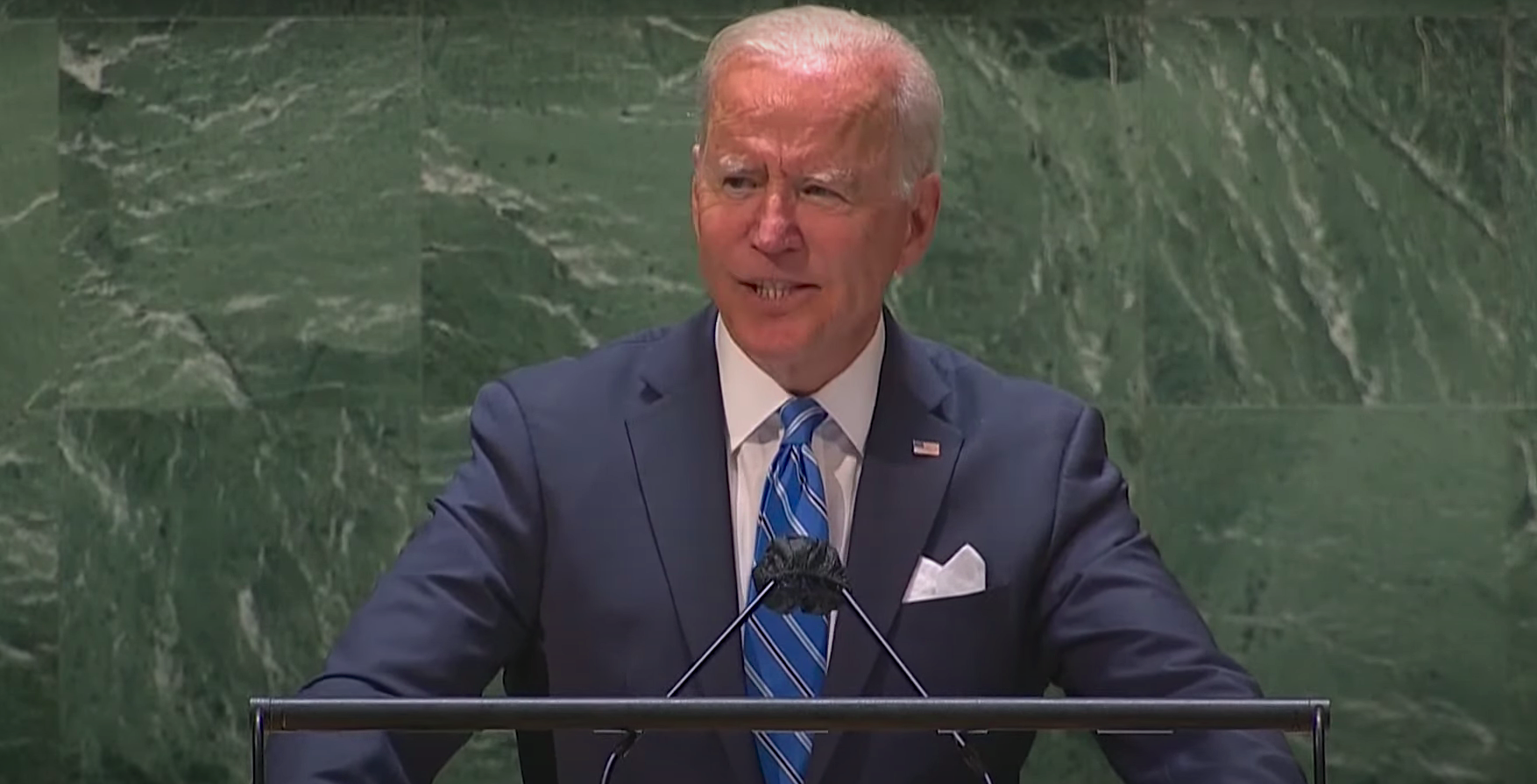

Joe Biden, in his first address to the United Nations General Assembly, told world leaders Tuesday: “I stand here today, for the first time in 20 years, with the United States not at war.”

According to the latest available White House war report, the U.S. was involved in seven wars in 2018: Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, and Niger. The U.S. withdrew last month from Afghanistan, so the number of current U.S. wars is likely six. Likely because in an age of so-called counter-terrorism operations it’s not entirely clear where U.S. forces are deployed.

U.S. involvement, for instance, in Niger came as a complete surprise. Biden has already carried out airstrikes in Syria and Somalia and he vowed to continue a drone war in Afghanistan. U.S. troops continue to occupy Syrian territory. There are officially 2,500 U.S. troops still in Iraq.

In any case, the United States is not at peace, as Biden implied. With 800 military bases and installations around the world the U.S. remains perpetually on a war footing

On the whole, though, Biden’s speech was the least bellicose to the General Assembly by a U.S. president in recent memory. He vowed that the U.S. would only use force as a last resort. “Bombs and bullets cannot defend against Covid-19 or its future variants,” he said. Indeed, the majority of his speech was devoted to fighting climate change and the pandemic.

By contrast, President Barack Obama seemed to be threatening the entire world in 2015 when he boasted from the U.N. podium: “I lead the strongest military that the world has ever known and I will never hesitate to protect my country or our allies, unilaterally and by force where necessary.” He blamed Russia and China for wanting to “return to the rules that applied for most of human history and that pre-date this institution.”

Obama said, “These ancient rules included the belief that power is a zero-sum game; that might makes right; that strong states must impose their will on weaker ones; that the rights of individuals don’t matter; and that in a time of rapid change, order must be imposed by force.” It is an apt description of America’s aggressive post-World War II history.

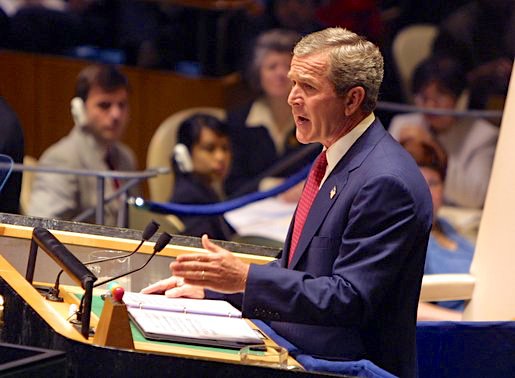

Bush Speak

George W. Bush was even more bellicose at the U.N., building his case for war in 2002 with a pack of lies at the institution that is supposed to be

“Today, Iraq continues to withhold important information about its nuclear program — weapons design, procurement logs, experiment data, an accounting of nuclear materials and documentation of foreign assistance. Iraq employs capable nuclear scientists and technicians. It retains physical infrastructure needed to build a nuclear weapon. Iraq has made several attempts to buy high-strength aluminum tubes used to enrich uranium for a nuclear weapon. Should Iraq acquire fissile material, it would be able to build a nuclear weapon within a year. And Iraq’s state-controlled media has reported numerous meetings between Saddam Hussein and his nuclear scientists, leaving little doubt about his continued appetite for these weapons.” dedicated to peace:

U.N. addresses by U.S. presidents are a chance for the self-proclaimed “leaders of the free world” to lay down the law of the jungle from the world’s bully pulpit.

Bullies don’t normally want to fight. They just want to get their way through intimidation by throwing their weight around. But just threatening war can have unintended consequences.

US ‘Diplomacy’

Biden told the U.N. he was keen on diplomacy. “We must redouble our diplomacy and commit to political negotiations, not violence, as the tool of first resort to manage tensions around the world,” he said.

But the words ring hollow, coming from a prominent supporter of the illegal invasion of Iraq. After just one term as U.N. secretary-general, after the Clinton administration essentially fired him, Boutros Boutros Ghali concluded that the U.S. had no need for diplomacy. He wrote in his memoir:

“Coming from a developing country, I was trained extensively in international law and diplomacy and mistakenly assumed that the great powers, especially the United States, also trained their representatives in diplomacy and accepted the value of it. But the Roman Empire had no need of diplomacy. Neither does the United States.”

Not to carry the idea of diplomacy too far, Biden, of course, told the world he’s still ready to use force whenever he thinks it’s necessary.

“Make no mistake: The United States will continue to defend ourselves, our allies and our interests against attack, including terrorist threats, as we prepare to use force if any is necessary, but — to defend our vital U.S. national interests including against ongoing and imminent threats,” he said.

He seemed to soften the blow by adding: “We’ll meet terrorist threats that arise today and in the future with a full range of tools available to us, including working in cooperation with local partners so that we need not be so reliant on large-scale military deployments.”

So Biden is for small-scale war. It is war nonetheless: the continuation of drone strikes and special forces in the ongoing Bush War on Terra that routinely kill innocent civilians.

Old Wars

Biden’s defense secretary, Lloyd Austin, said in April that future U.S. wars would not be like the “old wars.”

“The way we fight the next major war is going to look very different from the way we fought the last ones,” Austin said at U.S. Pacific Command in Hawaii. He said he spent “most of the past two decades executing the last of the old wars.”

“We can’t predict the future,” Austin added. “So what we need is the right mix of technology, operational concepts and capabilities – all woven together in a networked way that is so credible, so flexible and so formidable that it will give any adversary pause.”

After leaving Afghanistan last month Biden indicated the Pentagon’s attention would focus even more intently on Russia and China. The controversial, new U.S.-U.K.-Australia defense pact is clearly aimed at Beijing. Unlike Obama, Biden did not utter the words Russia or China in his speech. Instead he condemned them under the coded language of “authoritarianism.”

War is over. Welcome to the new war.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former UN correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and numerous other newspapers. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London and began his professional work as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

The artical was originally posted at Consortium News