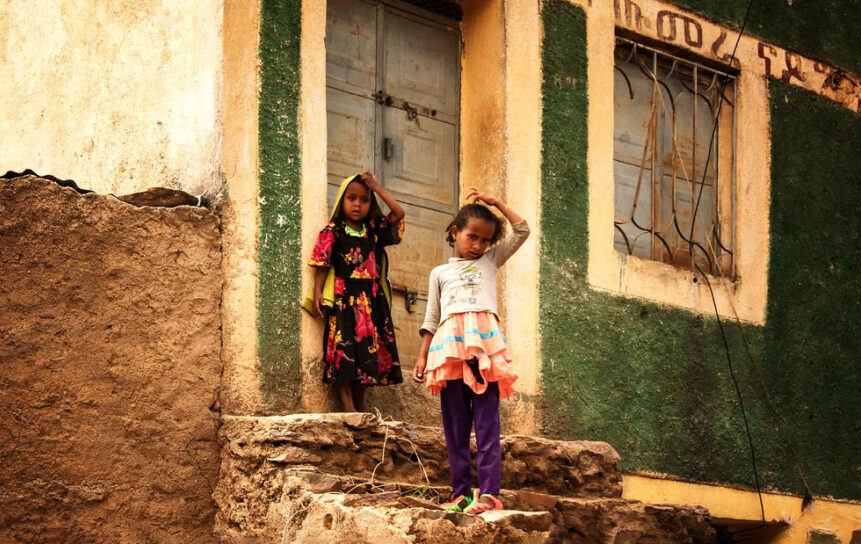

Girls in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, which has been at war since November 2020. Credit: Rod Waddington.

The state’s one-sided narrative has not just shattered Ethiopians’ shared understanding of reality but eroded the social fabric that held us together.

I grew up in the 1980s in Asmara, Eritrea. My father was a soldier serving the Derg regime that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991. Through this period, they were fighting a war on two fronts: one against the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) in Eritrea, the other against the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Tigray region.

I remember a key feature of this war being the role of the state media. There was only one TV station and a couple of radio stations, all of which hammered out the government’s propaganda day in and day out. It was part of our daily routine to hear the number of “enemies of the revolution” executed, battalions destroyed, and rebel units routed thanks to the heroic actions of gallant soldiers.

Even as a child at the time, however, I remember noticing the incongruity between these triumphant updates and the other stories we were told. Living in Kagnew military camp, we frequently heard of mothers becoming widows, of children becoming orphans, of soldiers never coming home, and of key positions being bombed repeatedly. We knew that everything was not as rosy as the government was saying, yet no one in the army dared question the state’s account.

This meant that often the only source of alternative news were radio stations controlled by the TPLF or EPLF. And despite the dangers of doing so in a notoriously brutal regime that encouraged everyone to spy on everyone else, my mother used to listen to Dimtsi Woyane, broadcast from Tigray, regularly. Each day, she would wait until my father left and then would carefully close the door, windows, and curtains. She would pull out the antenna from our Panasonic radio and tune it patiently until the Tigrinya voices became clear. She wouldn’t listen long – just enough to hear about the rebels’ advances and any cities or towns they had captured.

When my father returned from work, he would confidently recount the state’s version of events and insist the Derg was on the verge of finishing off its enemies. It was the most jarring experience I ever had. We lived in the same house, yet our sense of reality was completely divergent.

This shaped not just our interpretations of the war but our actions. Just two years before the fall of the Derg, my parents got an opportunity to buy a plot of land and build a house. My father was certain the regime would soon be triumphant in the war and that our lives would continue undisrupted, but my mother was sceptical. She turned out to be right. When the Derg fell in 1991, we were told to leave Eritrea. My parents lost all their savings and the land. I remember how even in its final days, the state’s TV and radio stations continued to claim the government was winning the war and encouraged more recruits to join the army.

Denial and dismissal

30 years later, Ethiopia is back at war. And once again, we are seeing the dangers of a single narrative, with the added explosive impact of social media. People in Tigray and their fellow Ethiopians may be sharing the same physical space, but their sense of reality has completely polarised.

When the war began in November 2020, the Ethiopian government imposed a communications blackout, jailed local journalists, denied access to international journalists, and embarked on a coordinated campaign on social media. Having silenced other voices, the state controlled the facts and narratives about the war.

I have family in Tigray and, with all lines of communication down, it took nearly three long months to find their whereabouts. Like thousands of others worrying about their loved ones, each of those days in the dark was spent in a fit of anxiety. I had no idea if my parents were safe as news trickled in from friends who learnt that their cousins or grandparents or nieces or uncles had been killed.

Amid the blackout, it took great effort for people in Tigray to get their own stories out, but they eventually managed. And when videos of massacres and reports of rape and destruction started to emerge, the outside world started to understand the gravity of the situation.

Many in Ethiopia, however, refused to believe their own eyes and ears. Several of my other friends and family members who weren’t from Tigray relied wholly on the state’s version of events and responded to anything that didn’t fit into this narrative with denial, dismissal, deflection, distortion, or victim-blaming. I again felt the disorienting and dizzying feeling I had as a child.

When the UN warned that 400,000 people in Tigray were facing famine, for instance, many non-Tigrayan friends dismissed their claims as exaggerated. When there were widespread reports that rape was being used as a weapon of war, they brushed them away, insisting that Tigray already had a problem with sexual violence or that the victims were militia members and so deserved it. When news emerged of the destruction of ancient cultural sites along with schools and hospitals, they suggested it was the work of the TPLF. To justify these beliefs, many went a step further in questioning not just the facts but the motivations behind those reporting them. They suggested that the journalists, news organisations and aid workers sounding the alarm – and anyone sharing their warnings – must be in cahoots with the TPLF or paid agencies of Western governments.

An appeal

It has been surreal to see how Ethiopia’s state media and affiliated influencers have managed to create an alternative reality in which even live-recorded killings do not register a sympathetic response. For those of us for whom the war has upended our personal lives, it has been deeply upsetting to see our compatriots treat massacres, rapes, and mass displacements as secondary to political and economic interests.

It has been even more devastating to see how a state-controlled narrative that dismisses Tigrayans’ testimonies as suspect and regards their misery as justified has led people to see their compatriots’ lives as dispensable. It has not just shattered a shared understanding of reality but eroded the very shared social and cultural fabric that held Tigrayans and other Ethiopians together. It has dehumanised an entire people. And now, as Tigrayan forces regroup in the war against federal forces, hate speech and discrimination towards Tigrayan civilians elsewhere in Ethiopia has intensified to even more worrying – but all too predictable – degrees.

If you’ve read this far, you probably don’t need to hear what I’m about to say. Those who do have probably already clicked away, having dismissed me as a TPLF agent or believing the violence I’m talking about is justified due to our imagined complicity in some past or current crimes. But if you have made it this far, let me tell you this: whatever the broader political or historical context, our pain, loss, death and distress are real. This may not fit neatly into the government’s single narrative of good versus evil, or in social media bubbles that reject nuance, complexity and, often, reality in favour of certainty. But the inconvenience of our suffering does not make it disappear.

If we are to escape the cycle of violence and death that has engulfed Ethiopia, we must start by rejecting simplistic narratives, no matter how compelling and appealing, that require us to lose sight of each other’s humanity.

Source: Africa Arguments