The Ethiopian government and Tigrayan leaders have signed a truce to end the two-year war that has caused catastrophic destruction across the region. The ceasefire will allow Ethiopia to receive urgent aid and financial assistance to combat the worst drought in 40years.

Ethiopia’s two-year war involving ethno-regional militias, the federal government, and the Eritrean military has a complicated genesis.

Despite being an ethnic minority, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the primary political party representing Tigray, has in the past dominated leadership coalitions and politics at the national level. Before Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, Tigrayan soldier-politician Meles Zenawi governed Ethiopia as an autocracy through a period of rapid development between 1991 and the year of his death in 2012. After his passing, the TPLF continued to govern Ethiopia until 2018.

But after national elections were postponed, in 2020 and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s term was extended the Tigrayan leadership started taking stirring. Their state council decided to hold local elections in direct defiance of federal orders, announcing that any interference would be a declaration of war.

Later that year, the Prime Minister ordered Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF) troops to the North for a military operation known as the Mekelle (named after the region’s capital city) Offensive in Tigray. Once Tigrayan troops (Tigray Defence Force, or TDF) retaliated and escalated their military response, the conflict turned into the civil war that is now known as the Tigray War.

Not only did the Prime Minister reject AU intervention, but soon the situation became mired with ethnic cleansing allegations and the failure to disclose the involvement of Eritrean troops. The latter was ironic considering the two countries’ equally bloody history.

According to an Amnesty International report released in February 2021, Eritrean troops targeted and killed over one hundred civilians and unarmed people in the Tigrayan city of Axum in December 2020. The Global Conflict tracker reports that, in 2021, Ethiopia reported 5.1 million internally displaced- the highest number in any country in any single year. To date, Tigray remains cut off from food, water, and medical aid.

Ceasefire declared between the principal parties

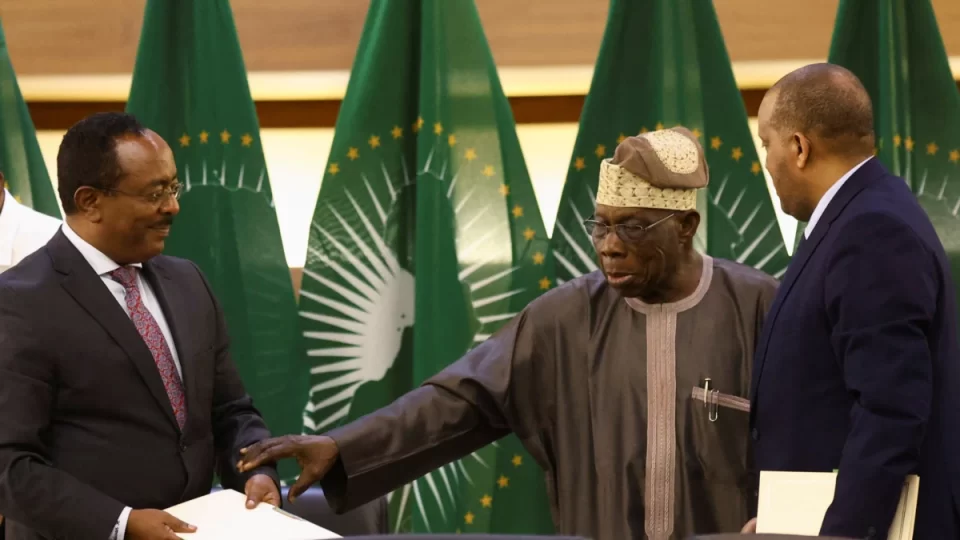

A truce between Tigrayan leadership and the Ethiopian government has been signed after formal peace talks in Pretoria, South Africa. Both parties were primed for a ceasefire, with the Tigrayans unwilling to lose more ground and the Ethiopian government under international pressure to end the war amidst a struggling economy and the effects of the worst drought in 40 years.

The parties have agreed on a “permanent cessation of hostilities,” the African Union mediator said.

On one side the Tigray forces agreed to a disarmament plan that they had previously rejected and the TPLF political party retracted its claim to be the elected regional government. On the other side, the government agreed to halt a massive military offensive even though its troops were making significant gains and momentum.

The government-TPLF joint statement also said the parties had agreed to implement a “Transitional Justice Policy framework to ensure accountability, truth, reconciliation, and healing.”

Former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, in the first briefing on the peace talks, said Ethiopia’s government and Tigrayan authorities have agreed on “orderly, smooth and coordinated disarmament” along with “restoration of law and order,” “restoration of services” and “unhindered access to humanitarian supplies.”

Despite this important milestone, there is continental and international scepticism as to whether the truce will take hold, and whether long-term peace will prevail. Concerns highlight the disarmament timeline, the role of Eritrean troops, a lack of clarity on what the proposed framework would achieve and how it would function, and the lack of accountability for crimes against humanity on both sides.

Muleya Mwananyanda, Amnesty International’s director for East and Southern Africa told Reuters, “At present, the accord fails to offer a clear roadmap on how to ensure accountability for war crimes… and overlooks rampant impunity in the country, which could lead to violations being repeated.”