Turkey may not necessarily spring to mind in relation to major international actors in Africa, but for years now Ankara has been quietly building ties with African nations.

According to African Business Magazine, the number of Turkish embassies in Africa has leapt from 12 to 42 since 2009. Trade has also risen between Turkey and the continent, growing from a mere $100 million in 2003 to $26 billion today.

On top of this, Turkey maintains a military presence in Somalia, where it trains local security forces, and holds a 99-year lease on the Sudanese island of Suakin. There are also plans to develop at least two Turkish military bases in western Libya, where Ankara’s intervention helped shift the conflict early last year.

Samuel Ramani, a doctoral candidate in international relations at the University of Oxford, told an Ahval podcast that Turkey’s presence in Africa, although not particularly new, had seen a growth in influence in recent years.

Historically, Turkey ruled over much of North Africa during the period of the Ottoman Empire, but influence faded dramatically after its collapse. This changed in 1998 with the “Action Plan for Africa”, which emphasised improving political, economic and cultural links.

Ramani, who authored an analysis on Turkey’s strategy in West Africa last year for the Middle East Institute in Washington D.C, said efforts to rebuild these relationships accelerated in the Justice and Development Party (AKP) era, particularly under former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, who Ramani describes as a “godfather” on the policy.

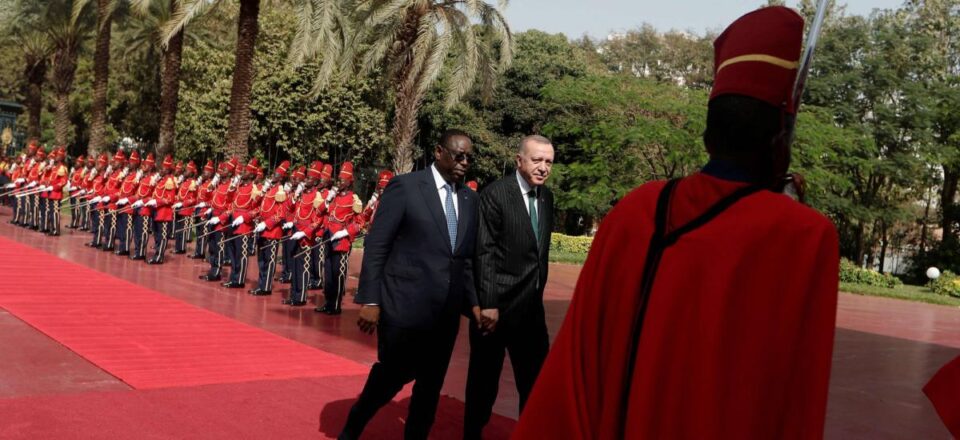

Since the AKP first came to power in 2003, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has visited 27 African nations and continues to express an interest in forging deeper ties with the continent.

“Turkey’s advantage in Africa over its rivals is its soft-power,” Ramani said.

Compared to former colonial powers like France or other more powerful outsiders like the United States and China, Turkey has fostered a comparably less pernicious image among Africans.

Ramani pointed to Somalia as an example. When famine struck the war-torn nation in 2011, Erdoğan was the first foreign leader to visit Mogadishu, bringing with him an entourage of business and political leaders, as well as celebrities to draw attention to the crisis.

Turkish charitable organisations assisted displaced Somalis, while development aid was invested in and beyond the capital city. More recently, Turkey helped Somalia pay-off part of its international debt, earning praise from local leaders.

This multi-pronged approach has succeeded in expanding Turkey’s credibility as a partner for other government in the continent, Ramani said. “There are certainly some African countries that are courting Turkish involvement in them beyond Libya and Somalia.”

But it would be a mistake to see Turkey role in Africa as coming entirely without strings attached. In particular, Turkey has pressured African governments to cut their links to schools or foundations connected to Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen.

Gülen’s followers in Turkey are accused of leading the failed 2016 coup attempt and have since been subject to a ferocious crackdown. But before spectacularly falling out with Erdoğan’s government, Gülenist played a role in building Turkey’s soft power in Africa through a school network that proved popular in several countries. Since 2016, Turkey has stepped up demands to see these schools closed, but several countries refused to comply.

Other governments, however, have cooperated, shutting down Gülen-affiliated institutions and in some cases aiding Turkish intelligence operations against alleged members of the group. And this showed how devoting attention to Africa has also paid off for Erdoğan at home, Ramani said.

“The very fact that African countries are closing these Gulenist schools magnifies their importance from the domestic Turkish point of view.”

Turkey’s litany of regional rivalries have also carried over into Africa. In Libya, Turkey has faced down an alliance of Russia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt in backing the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord against the rival Libyan National Army. Turkey is similarly competing with Russia and the Gulf kingdoms in the Horn of Africa.

But despite taking a more active role across the continent, Ramani said Turkey’s reach in Africa remains limited.

“It is erroneous to say Turkey is a great power in Africa,” he said.

This article has been adapted from its original source

Statements, comments or opinions published in this column are of those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Warsan magazine. Warsan reserves the right to moderate, publish or delete a post without prior consultation with the author(s). To publish your article or your advertisement contact our editorial team at: warsan54@gmail.com