India needs pragmatic leadership

The late Deng Xiaoping was once quoted as saying: “No matter if it is a white cat or black cat, as long as it can catch mice, it is a good cat.’’

If China’s economy has grown exponentially over the past 40 years, it’s due to this kind of pragmatic thinking by Deng, while summing up his vision at the Communist Party of China’s 12th Congress in September 1982.

Deng’s most notable achievement was to draw a line under the ideological excesses of the Cultural Revolution, which resulted in disaster for China as a nation.

Mao Zedong’s decision to launch the “revolution” in May 1966 is widely interpreted as an attempt to destroy his enemies. In fact, the Cultural Revolution crippled the economy, put the country in internal conflict, ruined millions of lives, and thrust China into 10 years of turmoil, bloodshed, hunger and stagnation.

China was paying the price of Mao’s idealism. No doubt it elevated Mao’s status as the most polarizing leader in Chinese history, but he failed miserably on the economic front.

His idealism was the reason behind millions of Chinese deaths. A country with tremendous potential and tremendous hope was virtually destroyed by the madness of one man. Thus a man who united China was also responsible for its destruction and fall.

Deng could never really condemn Mao’s ideological excesses publicly. But after seizing power from Hua Guofeng and the Gang of Four, Deng reasserted the need for economic pragmatism over and against political ideology.

Now, India is facing the same dilemma that China faced during Mao’s era: too much political idealism.

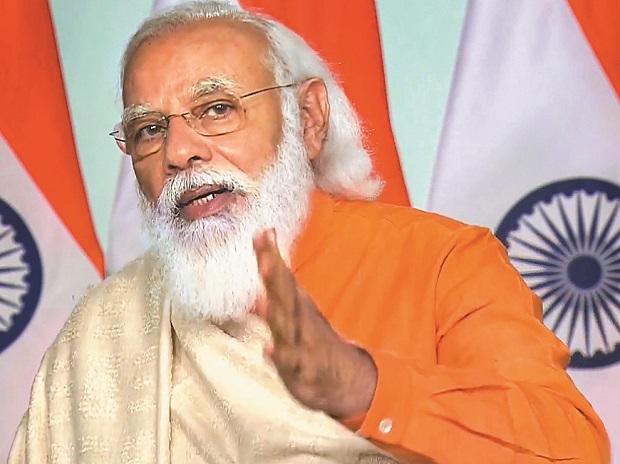

Modi, the Mao of India

In recent months, the second wave of the Covid-19 epidemic has brought India to its knees. Hundreds of thousands have died and the entire country is facing chaos and turmoil with the collapse of the health system.

The federal government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi has come in for harsh criticism for its handling of the crisis. Not only did he prematurely declare victory over Covid-19, he also allowed the week-long Kumbh Mela festival, where millions gather on the banks of the Ganges, to go ahead despite the risk of further spreading the virus.

And the irrationality didn’t stop here. He held massive rallies in West Bengal during the state election. Such was his hunger for power, he left no stone unturned to make sure his Bharatiya Janata Party won that election.

He broke all the Covid-19 protocols, just to defeat his political opponent. It was sheer madness equivalent to Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

But it was all in vain. On May 2, the incumbent Trinamool Congress (TMC) scored a thumping victory against the BJP. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s party won 213 seats compared with the BJP’s 77.

It was a big blow to the BJP, as it wanted a win in Bengal to be seen as a mandate for Modi’s leadership. But a close look will help us understand that BJP power has reduced substantially over the years, from its peak in 2018.

People have now started to realize that Modi’s erratic behavior has cost India a lot, from demonetization to the imposition of the goods and service tax (GST) with immediate effect, denying India’s 71 million small manufacturers time to set up the required accounting systems, to his decision to allow millions of people to attend a religious gathering in the midst of a pandemic, despite knowing the likely result.

Rather than focusing on improving the system, he focuses his energy on imposing his ideological beliefs on the system – quite like Mao, who envisaged a golden future for China with the Cultural Revolution.

But there is no quick solution to any problem. Particularly, in a system that is handling 1.2 billion people, the risk increases exponentially with the slightest change, so expert suggestions became quite critical. But Modi hardly gives any importance to any expert, be they economists or scientist, which we have seen during demonetization or the Covid-19 second wave.

That’s why all his decisions have proved to be irrational and a complete disaster for the country. Currently, Indians see hardly any hope for a great future, as the economy is shattering, and a new challenge in the form of a Covid third wave looms amid the pathetic performance by the current leadership.

But there is hope. India can learn from China and move from an idealistic leadership approach to a pragmatic one – a leadership and a system that are in correlation with the realities of the existing world order.

A new India needs a new vision

Humans are prone to hero-worship. But hero-worship takes an ominous turn when people start to idolize their leaders, as it gives a false perception to the people, that leaders with absolute power have the capacity to resolve any social and economic problem.

Throughout history, there are numerous examples where strong leaders proved to be disastrous for their country, whether Adolf Hitler in Germany, Josef Stalin in Russia or Mao in China. Today’s India is facing a similar situation.

Personality-based leadership has led to the massive centralization of power and thus the weakening of the democratic institution. More so, the current system cannot deal with the challenges of the 21st century. We have seen this during the Covid-19 second wave.

That’s why India needs to look for a better system, a system that enables all people to fulfill their potential and ensures that competent, capable, expert leaders are selected to govern the central challenges of society.

Meritocracy is the need of the hour, which is mainly of two types. The first includes social, occupational, or educational factors that ensure equality of opportunity, and the second type is political meritocracy, where leaders are selected based on competency rather than heredity or popularity.

Popularity or hereditary leadership is not a guarantee of policy success. So rather than focusing too much on the right leadership, the need is to focus on creating a system that helps us go in the right decision. The right answer to this question is something called “capunism.”

Democratic countries tend to be capitalist in nature, but today capitalism is failing and communism has hardly any relevance left in the 21st century. Capunism is a political system that employs the best attributes of both capitalism and communism.

It is a hybrid system where market forces and political forces work in tandem to support each other rather than exploiting each other for personal gains. The market should be solely in the hands of free enterprise within the purview of strong regulatory bodies.

It is commonly seen, as in India, that democracy tends to provide political freedom at the cost of economic freedom. Too much government intervention in policymaking kills the free market forces, a key prerequisite for an economy based on innovation rather than on monopolies either by government or private enterprise.

The focus should be given to the promotion of trade at local levels by encouraging decision-making at a local level rather than pre-defined goals and prices set by the government. Subsidies should be replaced with material incentives by looking at the overall productivity of the region.

Focus should be given to the integration of the rural economy by incentivizing more on home-made products than on agricultural output. This would allow us to shift from a completely agricultural economy to an agri-industry-based economy, the first step toward real industrialization of the nation.

But for that to happen, India needs a wise leadership at the top, which understands the importance of an efficient system rather than a strong leader. If China today stands tall both politically and economically, it is due to one wise leader and his belief in a strong system rather than a strong leader.

Deng Xiaping not only opened China’s economy but empowered its people with economic freedom. Thanks to this thinking, China has produced an abundance of millionaires, technicians, professionals and a skilled workforce over the last three decades, who no longer look for support from the government but act as a key pillar of the strength of their government.

Deng’s sensitivity to his country’s political culture while at the same time embracing capitalism led to a stepping stone for a new China. Currently, China is a bigger economic power than a political one. A shift in thinking from idealism to pragmatism changed the fate of a nation. Today’s India needs the kind of pragmatic leadership that Deng provided to China.