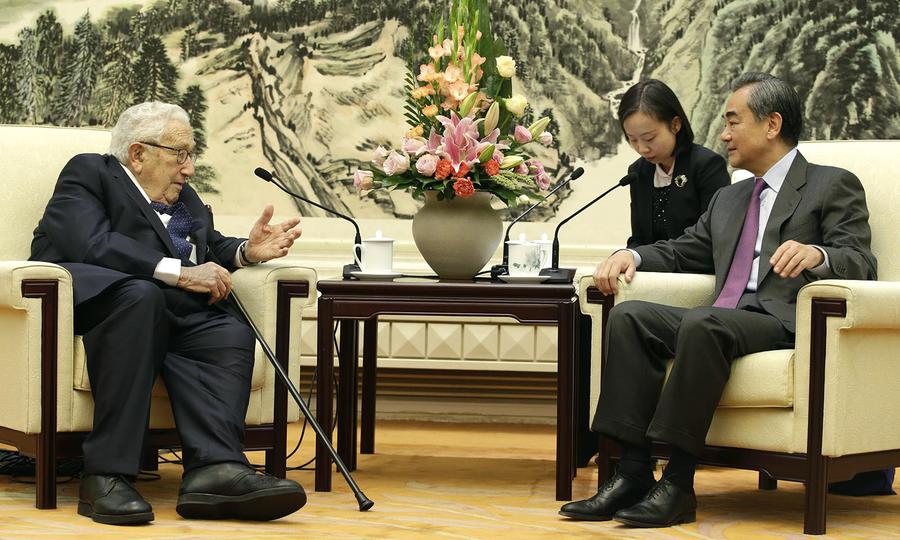

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) meets with former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 22, 2019. Photo: Jason Lee / AFP

Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger believes the US-China rivalry has entered dangerous waters

America and China are in “the foothills of a Cold War,” Henry Kissinger told a Bloomberg News conference in Beijing in November. “So a discussion of our mutual purposes and an attempt to limit the impact of conflict seems to me essential. If conflict is permitted to run unconstrained the outcome could be even worse than it was in Europe. World War I broke out because a relatively minor crisis could not be mastered,” the former US secretary of state added.

Kissinger’s analogy seems overwrought. For several reasons a Sarajevo-style trigger for conflict between the US and China is improbable. The European powers in 1914 had large standing armies ready to invade each other; if one power mobilized, its adversaries had no choice but to do so. As the Australian historian Christopher Clark demonstrated in his 2014 book The Sleepwalkers, Russia’s decision to mobilize irrevocably set the Great War in motion. The United States has a strong naval presence and military bases in East Asia, but nothing resembles the tenuous balance of power in Central Europe. China now has enough missiles to neutralize virtually all American assets in East Asia within hours of the outbreak of war, according to a recent evaluation by the University of Sydney. It also has the means to blind American military satellites, as Bill Gertz reports in his 2019 book Deceiving the Sky.

If the analogy to August 1914 in Europe seems strained, the popular “Thucydides Trap” argument comparing America and China to Sparta and Athens on the eve of the Peloponnesian War is even less appropriate. Athens and Sparta were unstable societies dependent on slaves and tribute, and had the capacity to destroy each other’s economic foundation in short order. Each side therefore had an incentive to initiate war. Game theory dictated a high probability of war. No such vulnerability exists in Sino-American relations.

The great, glaring difference between America’s confrontation with the Soviet Union in the 1980s and its rivalry with China in the 21st century is this: Russia’s civilian economy was stagnant, inefficient and corrupt, and unable to muster the range of technologies that America brought to bear on warfighting, despite the occasional excellence of Russian science and engineering. China’s civilian economy, despite important inefficiencies, remains the stupor mundi, the wonder of the world, 50 times larger in US dollar terms (and 80 times larger in purchasing power parity) than it was in 1979 when Deng Xiaoping introduced his market reforms.

Russia starved its consumer economy to feed its military, while China has produced both guns and butter. Unlike Russia, which devoted enormous military resources to keeping and equipping a vast land army, China has minimized its expenses on soldiery while spending lavishly on missiles, satellites, artificial intelligence, and other advanced technology that also has benefits for the civilian economy – just as America’s military and space expenditures did from Eisenhower through Reagan.

Nonetheless, a wing of the American foreign-policy establishment believes that it can weaponize China by promoting democratic movements, on the model that it mistakenly believes succeeded during the 1980s. It is encouraged by opponents of the Beijing regime such as the fugitive financier Guo Wengui (aka Miles Kwok) and Hong Kong Apple Daily publisher Jimmy Lai. Lai thinks that the US can force regime change in China, and made his case September 30 in The Wall Street Journal. Led by Florida Republican Marco Rubio in the US Senate and cheered by the usual suspects in the media, this current has elevated a comparatively minor problem in Hong Kong into a matter of national principle. Last week President Donald Trump – with evident reluctance – signed into law a bill passed by the US Congress with near unanimity to personally sanction Chinese and Hong Kong officials found to have perpetrated human-rights violations in Hong Kong and to revoke favorable trade conditions.

Some Chinese analysts have concluded that America’s concern over Hong Kong stems from a plot to destabilize China. A prominent Chinese political commentator told me via text: “I think none of the actors involved in this game – Beijing, the government of Hong Kong, the oppositions, the US – has made any mistakes. In the past months, all parties are collectively doing one job – transforming HK’s local unrest into a grand geopolitical confrontation between China and the US. So, any possible future outcomes of the HK issue would be directed by other bigger events from now on.”

Thus far, China’s response to the American legislation has been acrimonious in tone but restrained in practice. A Foreign Ministry spokesman said on November 28 that the bill “seriously interfered with Hong Kong affairs, seriously interfered with China’s internal affairs, and seriously violated basic principles of international relations. It was a nakedly hegemonic act.”

The spokesman added, “Since the return of Hong Kong to the motherland, ‘one country, two systems’ has achieved universally recognized success, and Hong Kong residents enjoy unprecedented democratic rights in accordance with the law.”

A Foreign Ministry statement said, “The US side ignored facts, turned black to white, and blatantly gave encouragement to violent criminals who smashed and burned, harmed innocent city residents, trampled on the rule of law and endangered social order.

“The egregious and malicious nature of its intentions is fully revealed. Its very aim is to undermine Hong Kong’s stability and prosperity, sabotage the practice of ‘one country, two systems,’ and disrupt the Chinese nation’s endeavor to realize the great rejuvenation.

“We remind the US that Hong Kong is part of China and Hong Kong affairs are China’s internal affairs and no foreign government or force shall interfere,” read the statement.

China’s response to date, though, has come down to suspending rest-and-recreation stops in Hong Kong by American warships and suppressing the activities of US non-governmental organizations that encourage the Hong Kong protesters. Beijing is far less worried about events in Hong Kong than some American observers imagine. Mainland Chinese never have identified with Hong Kong, which never was a Chinese city, but rather a British opium trading post that grew into a city of 7 million, a modest size by Chinese standards. Large numbers of Hong Kong demonstrators, for that matter, take to the streets with foreign passports in their back pockets and will emigrate rather than fight if matters get worse. The Hong Kong events have had virtually no impact on the mainland. On the contrary, every mainland Chinese I have asked about the matter insisted that the CIA is paying the demonstrators.

As the old joke goes, Hong Kong is a problem that can be solved in practice but is impossible in theory. The demonstrations have two root causes: arbitrary and autocratic governance, and a manipulated housing market that makes life unlivable for ordinary people. Hong Kong is a British city. Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula were ceded to Britain in perpetuity during the Opium Wars. For reasons that remain unclear, the government of British prime minister Margaret Thatcher in 1984 agreed to return Hong Kong and Kowloon to China when its lease on the New Territories expired in 1997, although it had no legal obligation to do so, and China did not want to take them back. “The Chinese did have concerns about taking over as they were so inexperienced in international governance,” a former UK Foreign Ministry official told me. The public record shows clearly that China did not seek the handover. I review the evidence in an essay published on December 2 at First Things.

Hong Kong’s travails, moreover, seem placid compared with the violence in other cities where young people have taken to the streets in protest against adverse conditions of life. Nineteen people died in recent riots in Santiago, Chile, long a poster-child for Latin American prosperity. In an October 23 analysis for Asia Times, I wrote: “No two cities could be more different than Hong Kong and Santiago. It is hard to find any common political theme. But they have something significant in common: Real estate bubbles in both venues have priced housing outside the means of ordinary people, and especially young people.”

Hong Kong has the world’s craziest real-estate market. According to the Numbeo database, the price-to-income ratio for Hong Kong homes is 50:1, by far the highest in the world (compared with the low teens in Europe and around four in the United States). That is Beijing’s fault. The Hong Kong executive has restricted the sale of land for housing development to benefit the island’s real-estate interests, while Beijing turned a blind eye to the deluge of illicit mainland cash invested in unoccupied luxury homes. President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign has reduced the outflows from the mainland to some extent; one no longer sees cash-counting machines at the Apple Store in Hong Kong central, where mainland money-launderers would exchange suitcases full of Chinese renminbi for hundreds of iPhones to be resold in the mainland.

Hong Kong would do best to emulate the Singapore model, which after all provided much of the inspiration for Deng Xiaoping’s original 1979 reforms. About 80% of Singaporeans live in public housing, only 40% in Hong Kong.

In short, it is well within Beijing’s power to provide remedies to the economic problems that motivated the protests. Beijing, however, cannot accommodate the antipathy of the Hong Kong majority to political affiliation with the mainland. Once China has acquired a territory by treaty, it cannot accept an infringement of its sovereignty anywhere without risking its sovereignty everywhere.

As I wrote in the cited First Things essay:

“China’s imperial structure is the source of its strength as well as weakness. Only a tenth of Chinese speak the court dialect Mandarin fluently; they converse rather in one of the 280 languages and dialects still spoken in China. ‘Chinese’ is not a spoken language but a system of written ideograms. The provinces have never shown affection for the tax collector in Beijing. What holds the country together, as it has since the founding of the Qin Dynasty (from which the country’s name derives) in the 3rd century BCE, is the ambition of its Mandarin caste and the central government’s investment in the infrastructure which controlled floods and irrigated the Chinese plains since the 3rd millennium BCE.

“That explains why Beijing is willing to go to war over the South China Sea. It is a fortiori demonstration in line with the Chinese proverb, ‘Kill the chicken while the monkey watches.’ If we are prepared for war over a few islands to which our historical claim is arguable, Beijing is saying, think of what we will do in the case of Taiwan.”

The neoconservatives, progressives, and assorted foreign-policy utopians believe that Hong Kong portends a replay of the 1980s, when (in their view) democracy movements in Eastern Europe brought down the Soviet Empire. Then as now, the neoconservatives make the mistake of thinking that they matter. Poland’s Solidarity movement, the church-centered protests in East Germany, and other protests among Russia’s satellites were a sideshow. The main event was military technology.

By 1982, when the US-built Israeli air force shot down Syria’s Russian-built air force over the Bekaa Valley, Russia knew that its massive investment in conventional weapons had gone wrong. By 1984, it knew that Russia’s economy could not keep up with America’s stupendous rate of technological advancement. A report (still classified) commissioned by the leading Russian plasma physicist Evgeny Velikhov and prepared at the Siberian branch of the Academy of Sciences at Novosibirsk early in 1984 informed the Russian military that US president Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative would push the envelope of defense technology to a dimension that Russia could not emulate. (This should not be confused with the 1983 “Novosibirsk Report” on the backwardness of Russian agriculture, whose contents long have been public.)

By 1984, moreover, the United States had succeeded in frog-marching its European allies into deploying the Pershing II medium-range missiles in Germany and Italy, fundamentally altering the strategic balance to Russia’s disadvantage.

That is why Russia opted for reforms, and ultimately lost its nerve in 1989. A strong and confident Russia would have asked how many divisions the pope had and simply killed the dissidents en masse, as it did in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The neoconservatives watched Russia fall and imagined that the magic of democracy had defeated the wicked sorcerer-kings of Moscow, and looked forward to the End of History as liberal capitalism inexorably spread throughout the world. This illusion was responsible for America’s plunge from the status of sole world superpower in 1989 to a prospective number two power in the second half of the 21st century.

If the United States wants to remain the pre-eminent world power, it will have to return to the policy that Dwight Eisenhower, John F Kennedy and Ronald Reagan successively adopted, namely the use of Defense Department resources to drive technological breakthroughs. During the Reagan years, the United States spent the present-day equivalent of $300 billion in basic R&D. Even if Congress appropriated that sum today it could not be spent: The corporate laboratories that did most of the work no longer exist, the engineering schools don’t graduate enough talent, and – as former House Speaker Newt Gringrich warns in a new book – the military-industrial complex is a barrier to innovation. The US has its work cut out for it, and Hong Kong is a distraction.

Asia Times